Personal Science Week - 260212 Notes

Taking notes in the age of LLMs

Back in PS Week 230302, we recommended a specific note-taking app, Joplin, for its open-source ethos, Markdown support, and end-to-end encryption. It was good advice at the time. But the world has changed dramatically since then — not just the tools, but the entire reason we take notes.

This week we’ll look at how AI has upended the way personal scientists should think about notes, why the format of your notes now matters more than the app, and what you should actually be writing down.

Why We Used to Take Notes

For most of history, we took notes to save facts we might need later. We clipped articles. We copied quotes. We bookmarked pages. The whole point was retrieval: you wrote it down because you couldn’t trust yourself to remember it, and finding it again in a library or filing cabinet was hard.

This created what Christian Tietze called the “Collector’s Fallacy” — the illusion that saving information is the same as learning it. We warned about this back in PSWeek230330: don’t fool yourself into thinking you really absorbed something just because you clipped it into Evernote. Most of those clippings were never looked at again. The act of collecting became a substitute for the act of thinking.

But at least the collector’s fallacy made some sense in the pre-AI world, because retrieval was genuinely difficult. If you didn’t save that article about sleep hygiene, how would you find it again? Maybe you’d remember the journal, maybe you’d reconstruct the Google search, but probably you’d just lose it.

That rationale has now completely collapsed. An LLM can find, summarize, and synthesize virtually any published fact in seconds. Saving a clipping “in case I need it later” is like keeping a drawer full of maps when you have GPS. The information isn’t going anywhere — and the AI is better at finding it than you ever were.

So if notes are no longer primarily for storing retrievable facts, what are they for?

Notes as a Record of Your Own Thinking

Here’s what I think has changed: the purpose of note-taking has shifted from collecting other people’s ideas to recording your own. Facts are cheap now. What’s expensive — what no AI can retrieve for you — is your own reactions, hypotheses, connections, and half-formed insights. The note you write after reading a paper, where you say “wait, this contradicts what I found last month with my sleep data” — that’s irreplaceable. The paper itself? Claude can find that in two seconds.

This is particularly important for personal scientists. Raw data matters, of course, but my interpretations, suspicions, and hunches matter more. I can always re-download a paper on melatonin. I can’t re-download the fleeting thought I had at 3am about why my magnesium supplementation seemed to correlate with my wakeup times only in winter.

In other words, AI has made the collector’s fallacy even more dangerous than before, because now it extends to the illusion that the AI “knows” your thoughts too. It doesn’t. It knows published facts. It knows what you’ve told it. But it doesn’t know what you were thinking while reading that article unless you wrote it down.

So: take fewer notes about what other people said. Take more notes about what you think about what they said. The first kind is now redundant. The second kind has become the most valuable thing in your entire knowledge system.

Files Over Apps

If the content of your notes has changed, so should the format. And here the shift is equally dramatic.

Steph Ango, the CEO of Obsidian, articulated a principle he calls “File Over App”: if you want your writing to still be readable on a computer from the 2060s, it should be readable on a computer from the 1960s. Apps are ephemeral; plain text files endure. (Read a much more rigorous analysis of this point in Martin Kleppmann and colleagues 2019 “Local-First Software: You Own Your Data, in Spite of the Cloud”.)

When you depend on apps (or worse, web apps), you are entrusting your data to cloud services that can shut down, change pricing, or lock us out. Vint Cerf, one of the inventors of the internet, has made the same warning. And anyone who’s lost data to a discontinued app — Google Trips, HealthifyMe, the old Zoe app — knows this isn’t theoretical.

The core idea is simple: your data should be more durable than any tool that touches it. If the tool dies, the data survives. If a better tool comes along, you can switch without losing anything. The files are the permanent thing. The apps are interchangeable views into those files

What to Do About It

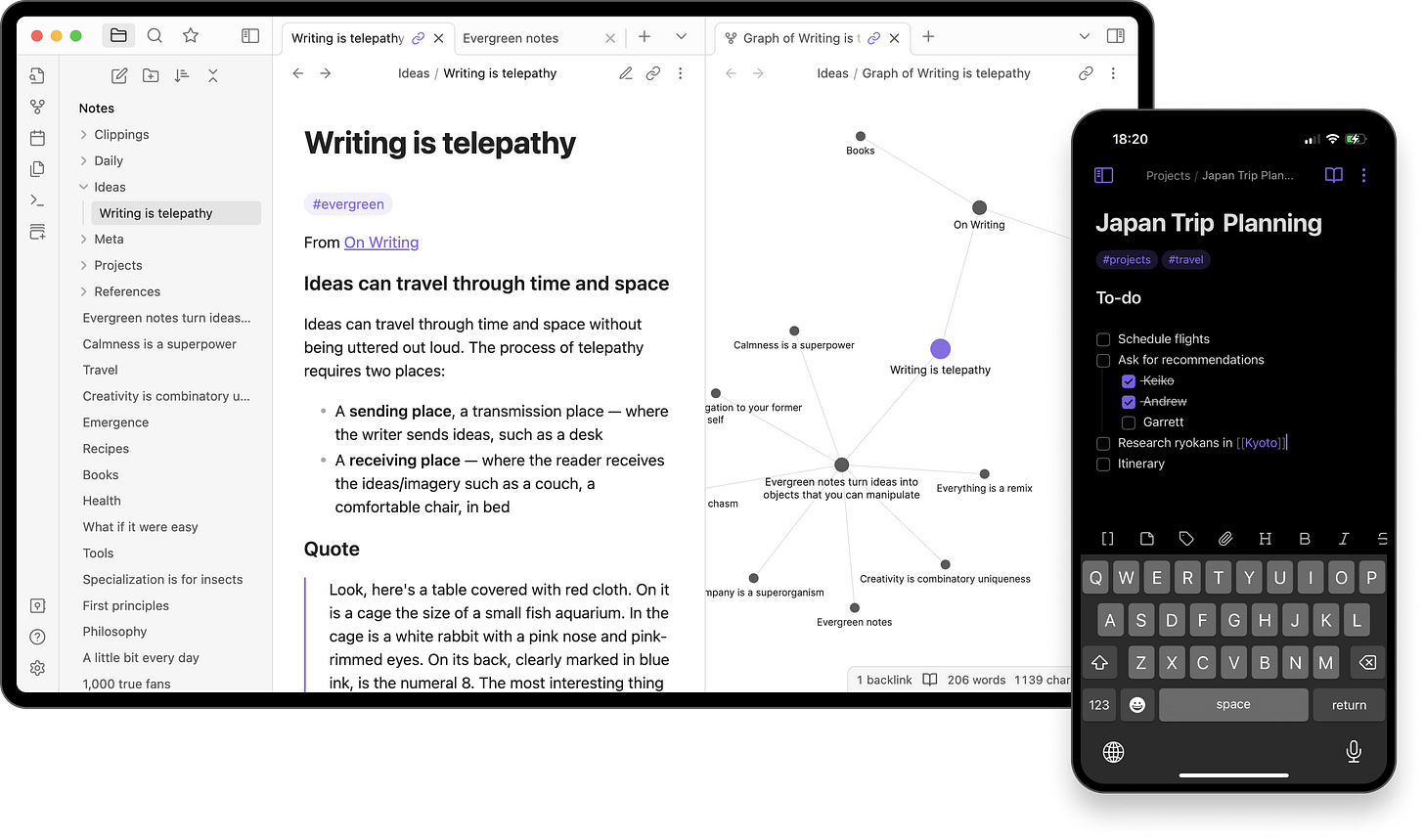

I switched from Joplin to Obsidian about two years ago. Obsidian stores everything as plain Markdown files in a normal folder — which means any tool can read them: grep, Python scripts, Git, and crucially, AI assistants. I now routinely point Claude Code at my notes folder and ask it to cross-reference my sleep data with my supplement experiments across two years of daily entries. As I described in PSWeek250814, my “repo” isn’t code — it’s self-experiment notes, health records, PDFs of lab results, and years of PSWeek drafts. It just works, because the files are right there.

Gary Wolf’s Zotero-to-Obsidian workflow and tools like Basic Memory (an MCP server giving Claude persistent vault access) show where this is heading. And if Obsidian disappears tomorrow, every note is still a readable text file.

But the tool matters less than the habits. Keep it simple — a plain text file you write in every day beats an elaborate system you abandon after a week. I still keep a daily food/sleep/exercise log in a single yearly text file. Write your reactions, not just the facts — when you read something interesting, write why it’s interesting, what it reminds you of, what you’d test differently. That’s the part no AI can reconstruct. Prefer plain files — Obsidian is my choice, but Logseq is fully open-source and file-based, and even a folder of .md files in VS Code works fine.

Personal Science Weekly Readings

Heying and Weinstein’s “Don’t Look It Up” argues that easy access to information can undermine empirical thinking skills if it replaces rather than supplements your own reasoning. The same caution applies to AI-assisted notes — the goal is to think better, not to outsource thinking.

Don’t forget the “Google Effect” we discussed in PSWeek260108: we tend to remember where to find information rather than the information itself. LLMs amplify this massively. If you’re offloading all your factual memory to AI, what remains uniquely yours is your thinking about those facts.

Martin Kleppmann et al., “Local-First Software: You Own Your Data, in Spite of the Cloud” (2019) — the rigorous academic case for why your data should outlive your apps, with seven ideals for local-first software.

Steph Ango, “File Over App” — the short, accessible version. Key line: “It’s a delusion to think [Obsidian] will last forever. It’s the plain text files I create that are designed to last.”

About Personal Science

There’s a pattern here that extends beyond note-taking. When Function Health wouldn’t let me export my blood test data (PSWeek240912), I was frustrated for the same reason: that data belongs to me, not to whatever app happened to collect it. When a CGM stores readings in a proprietary format, it limits what I can learn from my own glucose data.

File-over-app is really just data sovereignty applied to your own thoughts. Personal scientists already insist on owning their health data. We should insist on owning our knowledge base too — and now, thanks to AI, the stakes for getting the format right are higher than ever.

If you have a note-taking workflow that works well with AI tools, or if you’ve experienced data loss from a discontinued app, let us know.