Personal Science Week - 260108 Google Effect

Measuring whether technology makes us dumber

Technology has put every fact instantly accessible, to the point where it’s tempting to no longer remember things for ourselves. Why bother when you can just “Google” it?

This week I tried to measure my own Google effect as I speculate on what LLMs will do as they become more integrated in our lives.

The Original Google Effect

In 2011, psychologist Betsy Sparrow and colleagues published a provocative paper in Science called “Google Effects on Memory.” The findings were elegant and slightly alarming:

When we expect to look something up later, we don’t bother remembering it. Participants who believed trivia facts would be saved had significantly lower recall than those told the facts would be deleted.

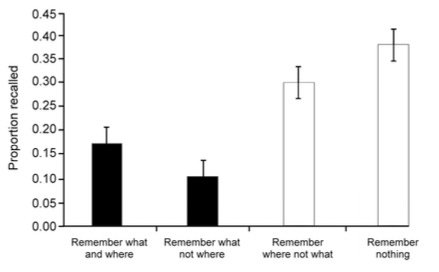

We remember WHERE better than WHAT. People were better at remembering which computer folder contained information than remembering the information itself.

Hard questions prime us to think about search engines. In a Stroop-style task, participants were slower to name the color of tech-related words (GOOGLE, YAHOO) after answering difficult trivia questions—suggesting their brains had already turned toward computers as the answer source.

Sparrow called this “transactive memory”—the same phenomenon that happens in couples where one spouse remembers birthdays and the other remembers directions. The internet had become our cognitive partner.

The Replication Problem

Before we panic about digital amnesia, an important caveat: the “Google Stroop” effect failed to replicate in a major 2018 study published in Nature. The researchers couldn’t reproduce Sparrow’s findings.

This doesn’t mean cognitive offloading isn’t real—the save/delete memory effects make clear intuitive sense and have been more robust across studies. But the specific mechanism remains contested.

This is why n=1 experiments matter. Population-level effects may wash out individual variation. Maybe the Google Effect is stronger in some people than others, depending on how much they’ve internalized search engines as cognitive partners.

Testing It On Myself

Rather than just read about the Google Effect, I asked Claude to build me a self-experiment tool based on Sparrow’s original methodology. Because I want to be able to compare my results to those of the original paper, I specifically asked that the test include similar tasks.

Think about 20 trivia statements (half “saved to folders,” half “deleted”)

90 seconds of math problems to clear working memory

Free recall: write down what you remember

Recognition test: old vs. new statements

Location memory: which folder held each saved item?

Stroop task: name colors of tech words (CLAUDE, CHATGPT, GOOGLE) vs. neutral words after hard vs. easy trivia questions

The whole test takes about 10 minutes.

Results

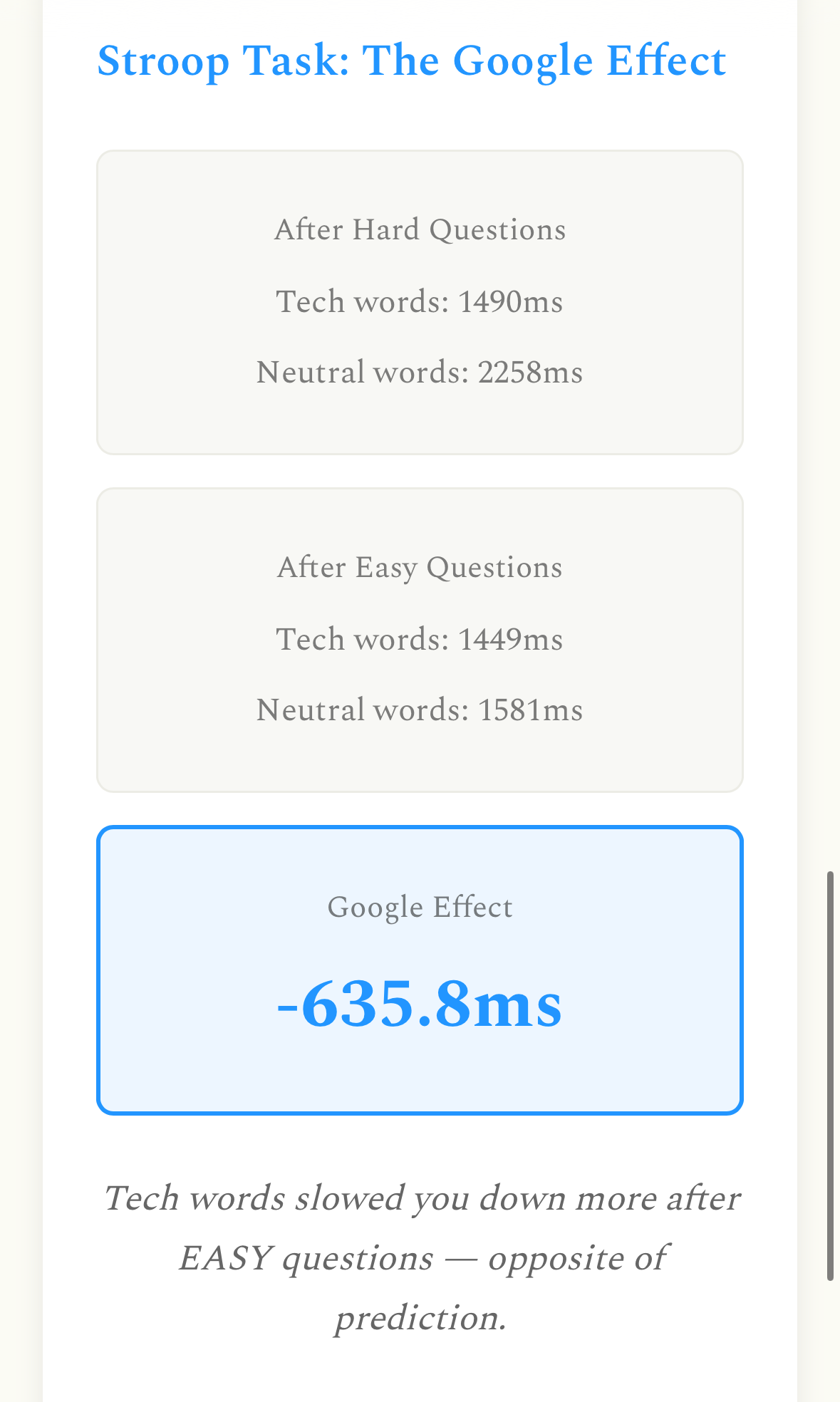

My results were ambiguous. Although in one attempt, the tech words slowed me down more after hard questions—consistent with the Google Effect hypothesis—in other attempts the results were negative.

I’m guessing that it’s a problem with the test itself. I’m trying too hard to replicate the design of the original paper rather than think from first principles about the effect I really want to measure.

Take the test yourself and see what you find.

From how to where to what

The idea behind the “Google Effect” is that technology has replaced the way we remember specific present-at-hand facts we need about our world. Instead of storing the fact itself, we store where to find that fact.

Google Maps changed how we get from one place to another because it’s just better than we are at knowing all possible routes and traffic. When we want to go someplace, we no longer care how we’ll get there; we just remember where we’ll get the directions: the Maps app. (I doubt most young people these days could find their way home from the grocery store if something happened to disable Google maps).

As I use LLMs more and more, I notice myself taking another step where I no longer even bother remembering where to look for an answer. I know I’ll be using the LLM, and I trust it’ll give me the answer. The only question is what I’ll do with the results.

Back in PSWeek250227, we wrote how LLMs have shifted the balance of personal science power from knowing how to do things to knowing what to do in the first place.

Google offloads the facts: recall, directions, phone numbers

LLMs offload the HOW: reasoning, synthesis, expression

If machines handle the HOW, what remains uniquely human? I think it’s the WHAT in a different sense—knowing what questions to ask, what problems matter, what to do with the answers.

Before LLMs, I never would have thought to ask “what’s the ratio of unmarried men to women in Seattle by neighborhood?” The question wasn’t worth the research effort. Now I can ask anything—and the question-space itself has expanded.

Maybe we’re not getting dumber. Maybe we’re reorganizing what we consider worth knowing.

But we still have to decide what we want to do in the first place.

Personal Science Weekly Readings

Speaking of LLMs and their affect on our brains, several groups are actively trying to investigate whether LLMs are making us dumber (eg. the 2025 MIT “Brain on ChatGPT” study) . But these studies tend to be full of researcher bias, and LLMs are changing so quickly that I’m not sure I believe any of the results.

Instead, I think it’s better to focus on the more timeless ideas of philosophers who have been pondering this problem for a long time. See Extended Mind Thesis - Clark & Chalmers 1998.

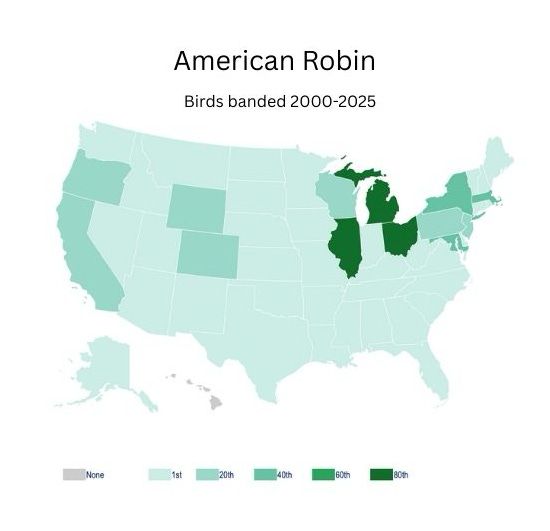

Speaking of other things to track, did you know you need a federal permit to put a band on a wild bird. There’s no fee, but you have to renew every three years. It applies to almost any bird you can think of. But the good news is that this enables a national database showing where all the birds are. Here’s a map of American Robin

But there are no regulations on banding an insect (like butterflies)

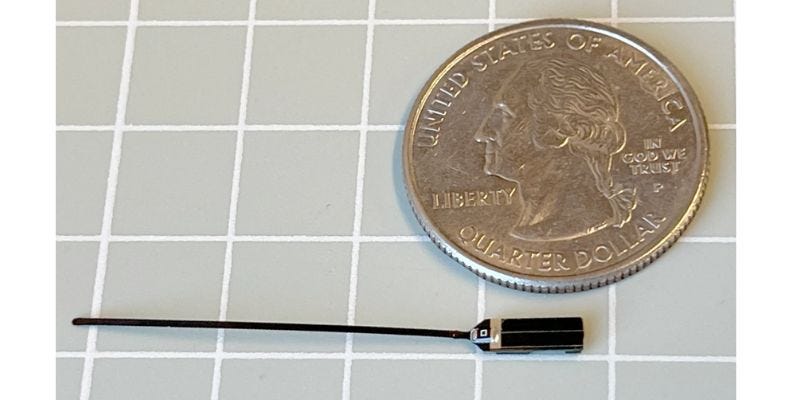

Cellular Technologies will sell you a $175 BlūMorpho – Ultralight 2.4GHz Radio Tag that fits on a butterfly wing and can be detected from 300 feet away with special bluetooth receivers. For $2/month you can register your tag and get notified when it shows up on their network of sensor stations.

About Personal Science

Personal scientists approach their own biology and behavior with the same rigor professionals apply to research questions: careful observation, controlled experiments, and healthy skepticism.

We’re particularly interested in what happens when you test things on yourself rather than waiting for the population-level studies. Sometimes the effect is real but too small to matter. Sometimes it’s real for you but not for the average person. And sometimes the act of measuring changes the behavior more than any intervention.

If you tried the Google Effect test and want to share your results, let us know. We publish these weekly updates for anyone who prefers nullius in verba — take no one’s word for it.

Do people really use IT in navigating to places they go all the time, like grocery stores? I can't imagine doing that but am admittedly eccentric in not using the GPS functions in my car at all, even when visiting places I've never been. On those, however, I will see where they are located using Google Maps before starting out.

This is really interesting. I have had discussions related to this about why I prefer paper books over electronic books. I know that my memory is visual and spatial. I write notes in the margins and can remember where "approximately" in the physical space of the book my note exists. I can't do this with an electronic book. I lose a lot of the material fairly quickly from an eBook unless I am using it regularly. With my physical books I interact with them periodically in search of my margin notes and I add to them. I have never done this with an electronic book. I do find that using Ai has an impact in terms of "remembering" unless I am going back to the conversation and continuing or using it in other ways - copying to a document, incorporating it in to other writings or material that are original. With GPS, my husband used to use it for everything no matter that he knew where he was going. I rarely use it because I think it does affect my own navigation instincts. Great article!