Personal Science Week - 251203 Mistakes

I was wrong

In PSWeek251113, I analyzed a fellow personal scientist’s metformin experiment using two different LLMs. I cross-checked my conclusions. I felt pretty confident, but I was wrong.

This week we’ll examine my errors, then look at how even professional scientists make similar mistakes — sometimes with far bigger consequences.

My Autocorrelation Mistakes

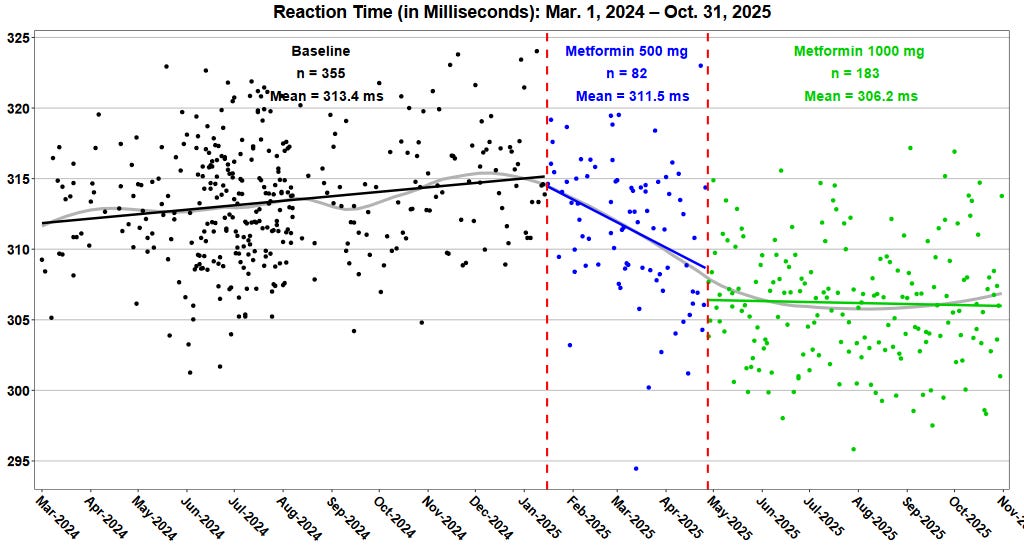

In PSWeek251113, we discussed Alex Chernavsky’s metformin experiment, where he tracked his cognitive reaction time while taking metformin for pre-diabetes. I fed his data into Claude and ChatGPT to check for autocorrelation. Both confirmed a statistically significant effect. Then Alex emailed me, confused about my comment about “missing data”. He had published all of his data, and I had the full copy for my analysis. So why did I think something was missing?

The problems: Claude completely overlooked that Alex had tested three dosage levels (baseline, 500mg, 1000mg) — not two. This dose-response design is far stronger evidence, but I missed it entirely. My claim about “missing data” was just a Claude hallucination related to the way the data was tagged — in fact there was no gap. And my cross-check with ChatGPT failed because I only asked about autocorrelation, not the underlying data structure. ChatGPT had noticed the three conditions; I just didn’t catch the discrepancy.

The correction: When properly analyzed, Alex’s metformin effect is more robust than I initially suggested. The dose-response pattern (500mg → small improvement, 1000mg → larger improvement) substantially strengthens the causal inference. I owe Alex an apology.

The lesson: AI tools are powerful, but they don’t replace careful thinking. They amplify whatever approach you bring — including sloppy verification. Using two LLMs to cross-check isn’t enough if you don’t examine what both are actually saying.

Professional Scientists Make Mistakes Too

My errors are minor compared to some famous scientific blunders that have shaped public understanding for decades.

The Replication Crisis

Studies that fail to replicate are cited up to 300 times more often than those that successfully replicate. The more you’ve heard of a study, the more skeptical you should be.

Consider some famous casualties:

Ego Depletion: The idea that willpower is a limited resource — use it up resisting cookies, and you’ll cave to cake later. Roy Baumeister’s research spawned over 600 studies and a bestselling book. Then came the reckonings: a 2016 multi-lab replication (23 labs, 2,141 participants) found exactly nothing. A 2020 follow-up (36 labs, 3,531 participants) concluded the data were “four times more likely under the null.” It was completely wrong.

Power Posing: Stand like Superman for 2 minutes → boost testosterone and confidence. Amy Cuddy’s TED talk has 60 million views. A replication with 200 participants found no hormonal changes, no behavioral effects. The lead author later publicly disavowed the findings.

Stereotype Threat: Awareness of negative stereotypes impairs test performance. Applied to real schools, cited endlessly in education policy. Multiple preregistered replications failed. The effect may be “no different from zero.”

Facial Feedback: Smiling makes you happier (the “pencil in your teeth” study). A replication across 17 labs couldn’t confirm it.

The pattern: the studies you’ve heard of are disproportionately likely to be wrong.

Popular vs. Unpopular Findings

Much as scientists like to think they simply “follow the data”, some data is more welcome than others. Is there any future for a professional who studies, or anything that finds the “wrong” answer to questions about IQ differences across races or on questions related to homosexuality or transgender issues? What about evidence that death counts should be revised up or down for historical events such as the Holocaust, the Chinese Great Leap Forward, or the US-Iraq War. We already know the “correct” answers, don’t we?

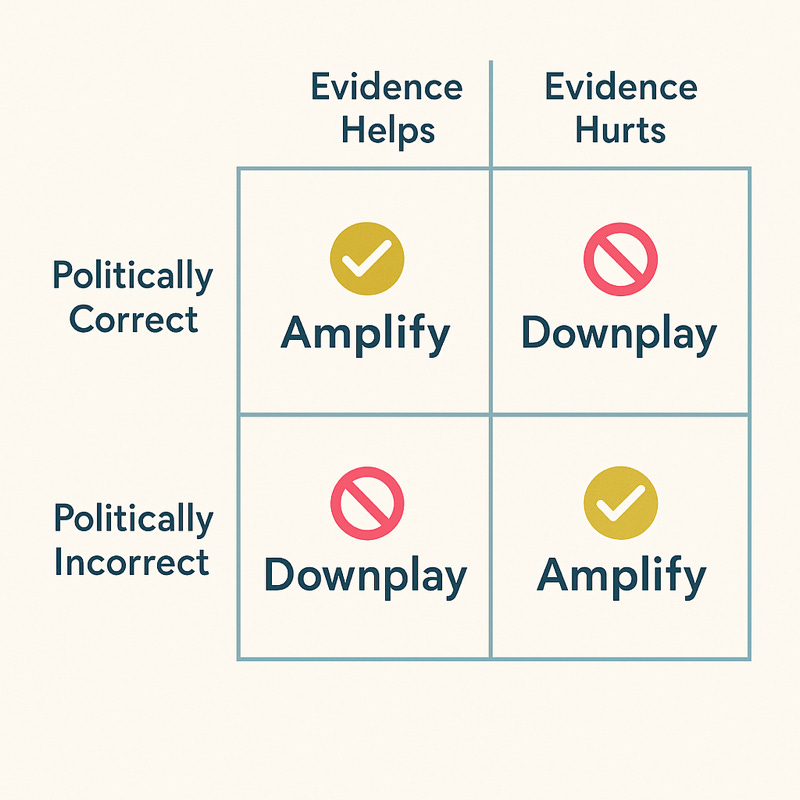

Remember the 2023 headlines about women hunters in “the vast majority” of hunter-gatherer societies, promoted in top journals like Science, Scientific American, Smithsonian and elsewhere. But a 2024 debunking found blatant errors: selective filtering, no distinction between rare and common events, conflation of assistance with actual hunting. The debunking got far less coverage. Findings that fit popular narratives get amplified; corrections get buried.

Sometimes Even the Corrections Are Wrong

In PSWeek250724 we discussed the spinach-iron myth. When it was debunked, papers claimed the myth originated from a 1930s decimal point error. But when traced to its source, this turns out to be an academic urban legend. The decimal point error never happened.

You’ve heard how Barry Marshall infected himself with H. pylori to prove ulcers are bacterial, defying a stubborn establishment. Except most scientists already knew microbes caused ulcers — they just couldn’t find a good treatment. The myth persists because everyone loves a David vs. Goliath story. (See more examples at PSWeek241121)

My favorite: In 2023, researchers advocating for better scientific practices had to retract their own paper when their methodology was found flawed. Their statement: “We are embarrassed.”

What Personal Scientists Can Do

The lessons from my mistakes and these professional examples:

Check primary sources — I should have examined Alex’s data structure myself instead of trusting LLM interpretations.

Be suspicious of claims that seem too convenient; the spinach myth persisted because it was a tidy story, and my “missing data” claim fit a neat narrative that happened to be false.

Verify your verification by examining what your sources actually say, not just whether they agree.

Remember that citation count doesn’t equal truth — popular myths get cited more than boring facts, and failed replications more than successful ones.

Apply the same skepticism to prestigious journals that you would to any other source.

And be willing to correct yourself publicly, even when it’s embarrassing. Science only works when we’re honest about what we got wrong.

Personal Science Weekly Readings

Temporal Validity: Political scientist Kevin Munger introduces the concept that a research finding may only be true at a particular point in time — another form of “mistake” when we assume findings are permanent.

Al Gore’s 2006 Predictions: Speaking of temporal validity, how did An Inconvenient Truth hold up? Directionally correct on long-term trends like CO2 increases, but “a bit over-the-top“ on specifics like “within a decade, there will be no more snows of Kilimanjaro” — which missed the mark.

The Case Against Publicly Funded Science: This provocative piece notes replicability problems indicate significant waste. Private R&D dwarfs public investment — roughly 70% of science is financed by corporations and charities.

About Personal Science

Personal scientists are skeptical about everything — including ourselves. We make mistakes. The question is whether we catch them, correct them, and learn from them.

The good news: Alex’s experiment is actually stronger than I suggested. The dose-response pattern is compelling evidence something real is happening. The better news: this iterative correction is exactly how science should work. You publish, get feedback, revise. It’s not pretty, but it converges on truth — if you’re honest about your errors.

Nullius in verba — take nobody’s word for it. Including mine.

If you’ve caught mistakes in your own analyses, let us know.

Speaking of mistakes, you'll note that although we're supposed to deliver on Thursdays, I appear to have sent this week's post a day earlier than intended. Oops!

Richard, thanks for the nice write-up.