Personal Science Week - 251113 Autocorrelation

Using LLMs to study a link between metformin and improved cognitive performance

Self-collected data is often a time series, where you track something like sleep or calories daily or weekly. A proper analysis of the results requires careful attention to how measurements taken on one day influence the next.

This week we’ll look at an interesting finding from one personal scientist to show how how easy it is to use Large Language Model chatbots for important insights that previously were possible only with heavy statistics training.

Your body doesn’t have a reset button. When you measure something about yourself today—reaction time, blood glucose, mood—that measurement doesn’t exist in isolation. It carries echoes of yesterday, which carries echoes of the day before. This is autocorrelation, and ignoring it is one of the most common mistakes in personal science.

Most statistical methods assume your data points are independent—that measuring yourself on Monday tells you nothing about Tuesday. But biological systems have memory. Your sleep quality affects tomorrow’s cognitive performance. Your microbiome composition shifts gradually, not randomly. Your exercise recovery follows predictable patterns. When you track these things over time, adjacent measurements correlate with each other, often strongly.

Fortunately there are ways to correct for auto-correlation, and even more fortunately you can now easily do the calculations using your favorite LLM chatbot. This week I tried this by working through an example from another personal scientist.

Personal Scientist of the Week

Back in PSWeek250703 we described the “Brain Reaction Test”, aka BRT or RT, developed by the late Seth Roberts as a way to detect how the brain responds positively or negatively to personal environmental changes like food, supplements, activity, and more.

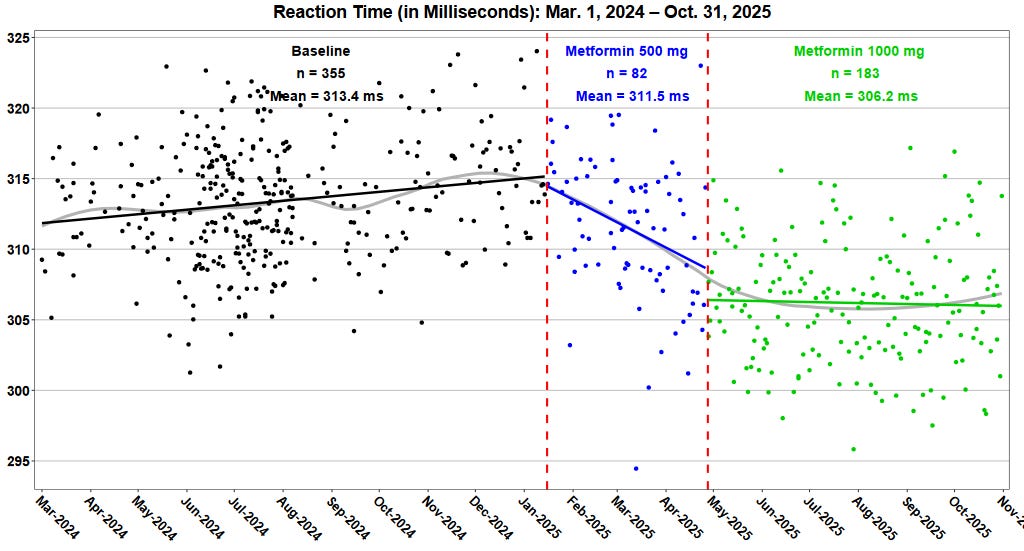

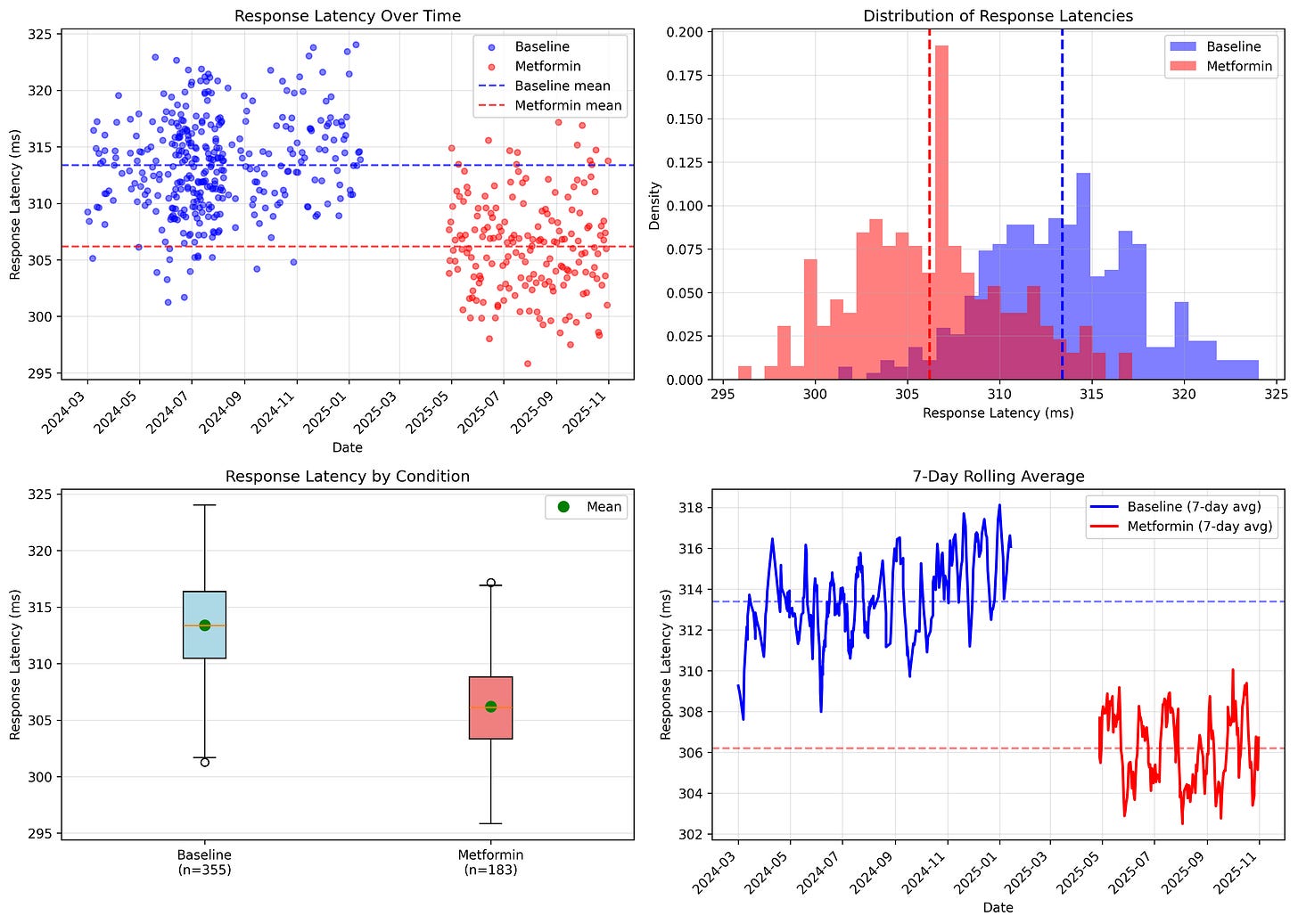

Now Alex Chernavsky has found what appears to be a clear effect on RT from taking metformin as a treatment for pre-diabetes. He’s been measuring daily for years, and noticed this trend in his cognitive performance (lower numbers are better):

Like all good scientists, Alex lets you download his raw data, which I fed into both ChatGPT and Claude. Both LLMs were able to replicate his results: yes, based on his data it’s true there’s a statistically valid effect.

Despite the clear evidence of an effect, there are some important caveats:

The noise problem: The slight improvement of ~7 ms (standard deviation, aka SD) is tiny, especially considering that his normal SD ≈ 4–5 ms. As he himself points out, that’s below the threshold of subjective perception and sits right at the edge of typical measurement noise. Without calibration checks or instrument stability tests, it’s unclear whether this represents a real cognitive change or just device drift.

The autocorrelation problem: The analysis treats each session as if it were unrelated to every other session. But cognitive performance doesn’t work that way. Your reaction time today correlates with your reaction time yesterday, which correlates with the day before. This autocorrelation means the effective sample size will be much smaller than it appears.

Although autocorrelation is a big issue with this data, it’s also straightforward to correct for statistically and again, both LLMs are eager to run the numbers.

What Happens When You Account for Autocorrelation

It was easy to confirm the statistical significance of Alex’ initial calculations, and it was just as easy to use the same chatbot to do the next step: according to my two LLMs independent calculations, Alex’ data shows significant autocorrelation (Ljung-Box test p = 0.007, Durbin-Watson = 1.76 indicating positive autocorrelation). ChatGPT recommended a model using GLSAR with AR(1) errors:

Even accounting for the autocorrelation, there’s still an effect

Treatment effect: Remains essentially unchanged at -6.1 ms (vs -6.0 ms corrected)

Standard errors: Increase by 12.5% (0.70 → 0.79)

Confidence intervals: Widen by 12.5% (2.74 → 3.09)

Statistical significance: Still p < 0.000001

The AR(1) coefficient is 0.118 — meaning each session correlates with the previous one at r ≈ 0.12. This is relatively weak autocorrelation (I’d expected stronger given the nature of cognitive testing), but it’s still statistically detectable and enough to inflate the naive analysis.

Bottom Line

The metformin effect is more robust than I initially suggested — it survives the autocorrelation correction. However, the 12.5% increase in uncertainty is non-trivial and demonstrates the general principle: ignoring temporal structure makes your results look more precise than they actually are.

Consequence for this data set: Even with proper autocorrelation modeling, the effect remains statistically significant. But this doesn’t address the other fundamental issues:

Time confounding — metformin phase comes after 10 months of baseline, any secular drift is confounded with treatment

No reversal — without an A-B-A design, causality remains ambiguous

Practical significance — 6 ms is still below perceptual threshold

Missing data — what happened February-March 2025?

The autocorrelation correction makes the statistics more honest, but doesn’t fix the experimental design problems. This is still hypothesis-generating pilot data, not definitive evidence.

By the way Alex has been testing himself daily for years using his own Windows app (free download), but if you want an easier way to try RT, you can a (free) online version at brt.personalscience.com on your phone or any browser.

Personal Science Weekly Readings

Speaking of metformin, our friend and fellow personal scientist Nita Jain spent a lot of time looking into this for herself and concluded that metformin has a dark side: it can encourage growth of pathogenic oxygen-hungry gut microbes.

Microbiome scientist Brett Finlay and daughter Jessica Finlay wrote an excellent book The Whole Body Microbiome describing the process in much more detail. They point out that metformin doesn’t work if injected directly into the bloodstream—more evidence that it works by affecting gut microbes.

You may have heard of metformin as a potential anti-aging supplement, but that’s old news. Peter Attia in Research Worth Sharing Oct 2025 points to Probiotics and synbiotics reduce diabetes-associated inflammation a meta-analysis of 22 RCTs and concludes (in the fancy language only Peter Attia can produce):

The initial promise of metformin as a geroprotective agent for the general population, though, has mostly failed to materialize.

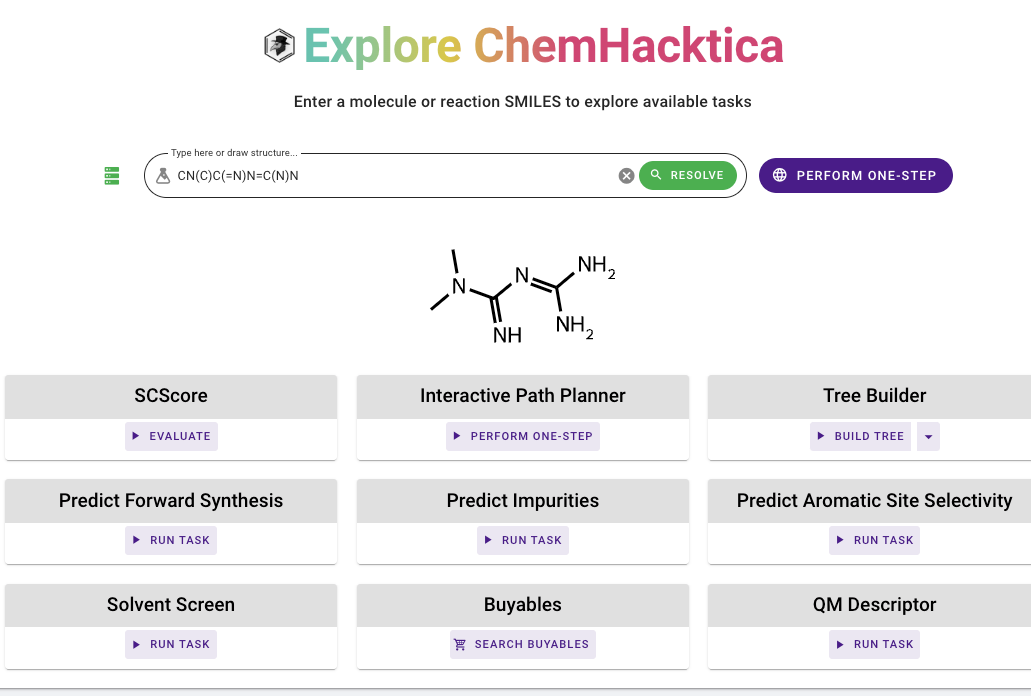

Finally, if you want to make your own metformin, I recommend you Explore Chemhacktica. Here’s what happened when I punched in the chemical code for Metformin

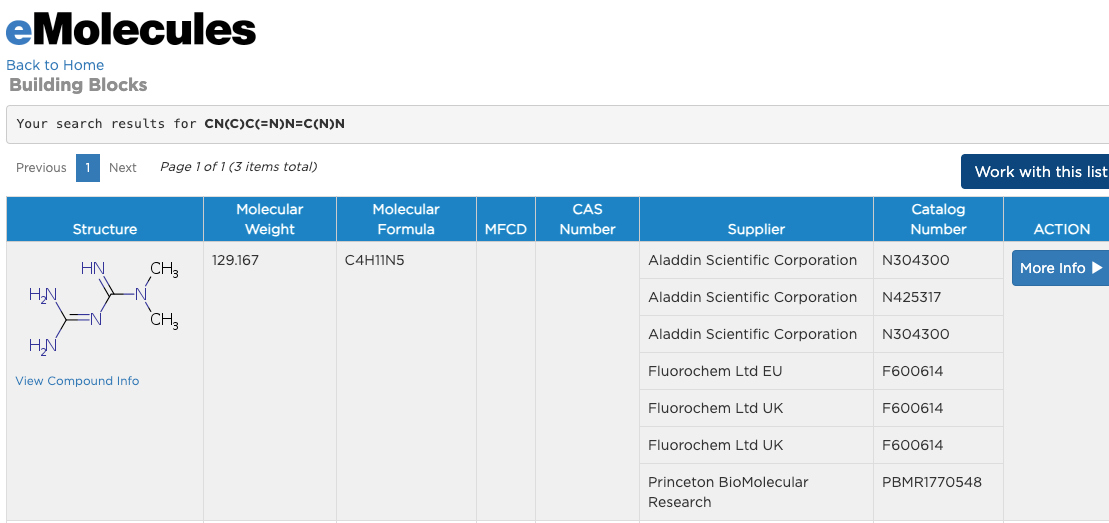

and it also generates a list of vendors who will sell the various ingredients required:

Enjoy!

About Personal Science

Personal science means applying scientific methods to questions about your own life—especially health, productivity, and wellbeing. Rather than waiting for professional researchers to study your specific circumstances, you become both scientist and subject, running n-of-1 experiments to discover what actually works for you.

We publish this short summary each Thursday. If you have other topics you’d like to discuss, please let us know.

The use of LLMs to handle autocorrelation in time series data is really clever. It democratizes acces to complex statistical methods that used to require specialized training. Alex's metformin experiment is a great exaple of personal science in action, even if the effect is below perceptual thresold. The fact that the result remains significant after correcting for autocorrelation adds credibility.