Personal Science Week - 250724 Academic Urban Legends

Untangling the great scientific spinach citation fraud

The famous “spinach is high in iron” myth reveals something troubling about how academic knowledge spreads.

This week we’ll unwrap one of my favorite academic papers, showing how citation practices can go wrong, even in peer-reviewed journals.

The Great Spinach Deception

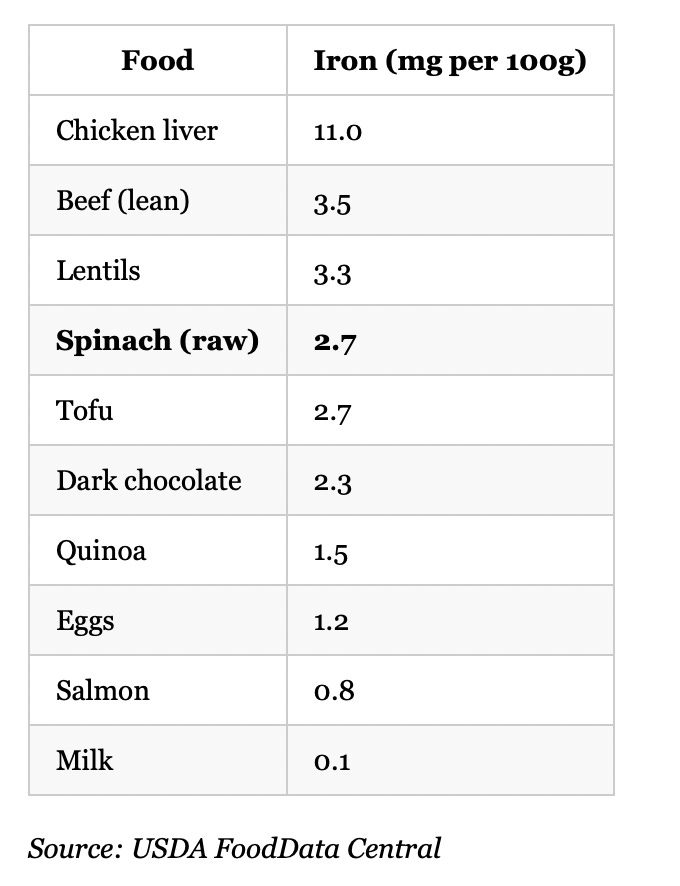

For decades, parents have tortured their children with spinach because “it’s high in iron.” But wait—it’s not true! Spinach has about as much iron as dark chocolate.

Worse, spinach contains oxalates that actually inhibit iron absorption, making it an even poorer choice for addressing iron deficiency.

So how did the rumor get started? The story goes that a 1930s decimal point error made spinach appear to have 10 times more iron than it actually contains, misleading generations of families and even inspiring Popeye’s legendary strength.

There’s just one problem: the decimal point error never happened.

Norwegian researcher Ole Bjørn Rekdal traced this academic urban legend to its source in a fascinating 2014 paper. What he discovered is a perfect case study in how sloppy citation practices create and perpetuate scientific myths—even among researchers who should know better.

The Citation Game Goes Wrong

The myth began innocuously in 1972 when nutritionist Arnold Bender suggested that spinach’s iron reputation “may well have grown from a misplaced decimal point.” This tentative hypothesis gradually morphed through multiple academic papers into established fact.

By 1981, hematologist Terence Hamblin wrote definitively in the British Medical Journal that German chemists had “shown in the 1930s that the original workers had put the decimal point in the wrong place.” But Hamblin provided no source for this claim.

The story went viral in academic circles. Researchers began citing Hamblin’s unsupported assertion, then citing each other’s citations, creating an impressive-looking web of “independent” confirmation. Soon the decimal point error was being cited without any reference at all—it had become “common knowledge.”

The Academic Whisper Game

Rekdal says academics often use these dubious practices when they encounter a claim with an existing reference:

Honest secondary citation: “According to Hamblin (1981), cited in Larsson (1995)…”

Hidden secondary source: Citing only Larsson without mentioning Hamblin

Reference stacking: Adding multiple secondary sources to make the claim look well-supported

Reference plagiarism: Citing Hamblin directly without actually reading his paper

Each approach introduces the possibility of error. When multiple authors independently misrepresent the same source in identical ways, it’s usually evidence of plagiarized citations rather than coincidence.

The Ironic Twist

Perhaps most ironically, many of the academics who spread this myth were writing about the importance of scientific rigor. K. Sune Larsson titled his paper “The dissemination of false data through inadequate citation"—while simultaneously demonstrating exactly this problem by misrepresenting Hamblin’s already-unsupported claims.

Read a more detailed and highly-entertaining version of the story at Scholarly Kitchen.

Personal Scientist of the Week

Speaking of spinach, did you know that the plant originated in Persia and wasn’t available in Europe until the Middle Ages? But even then they didn’t eat a whole lot of it, or other vegetables for that matter.

Atlas Obscura writer Sarah Laskow performed a diet experiment based on the medieval health manual Regimen Sanitatis Salernitanum (Download your own copy here). For nine days she ate like a 13th-century European: fresh eggs, red wine with meals, rich meat gravies, wheat bread, and cheese—while avoiding processed foods, sugar, and even coffee.

The medieval regimen was based on "humoral theory"—balancing the body’s four humors through hot/cold and dry/moist foods. But as nutritional therapist Andrea Grandson noted, they were actually “on the right track in terms of looking for nutrient density.” Eggs provide complete proteins, red wine offers antioxidants, and bone broths extract minerals from animal bones.

Laskow’s results? She felt great—energetic, well-rested, and never overstuffed. The diluted wine (mixed with water for safety and digestion) kept her “pleasantly buzzed” without impairment. Her only complaint: skipping breakfast made her lightheaded and prone to overeating later.

Personal Science Weekly Readings

Here are some related examples of how academic retractions and corrections reveal problems with the scientific literature:

Scientific Rigor Paper Retracted for Lack of Scientific Rigor: Researchers who advocated for better scientific practices had to retract their own paper when it was discovered their methodology was flawed. The authors stated: “We are embarrassed.”

The Replication Crisis Continues: Studies that fail to replicate are cited up to 300 times more often than those that successfully replicate, particularly in prestigious journals. The more you’ve heard of a study, the more skeptical you should be.

AI-Generated Academic Papers: European researcher Dmitry Kobak found that about 10% of 2024 academic publications were assisted by ChatGPT, up from just 1% in 2023. Look for overused words like “delve,” “meticulous,” and “prominence"—you might be reading an LLM.

About Personal Science

The spinach story reminds us why personal scientists must remain both open-minded and skeptical—even toward peer-reviewed research. As Rekdal notes, the digitization of academic literature has made it easier to expose citation problems, but has also created new opportunities for “academic shortcuts.”

Key takeaways for personal scientists:

Check primary sources whenever possible

Be suspicious of claims that seem too neat or convenient

Remember that citation count doesn’t equal truth—popular myths get cited more than boring facts

Apply the same skepticism to prestigious journals that you would to any other source

False information is surprisingly common, and can spread far and wide even through supposedly rigorous academic channels when researchers take shortcuts with their citations.

We publish each Thursday insights for anyone who wants to apply scientific thinking to personal questions rather than simply defer to authority. If you have other questions or topics you’d like to discuss, please let us know.

"Speaking of spinach, did you know that the plant originated in Persia and wasn’t available in Europe until the Middle Ages? But even then they didn’t eat a whole lot of it, or other vegetables for that matter." What!?