Personal Science Week - 260205 Supplements

How to tell which supplements are good, plus where your prescriptions are made

Our previous PSWeek260122-Trends mentioned the huge variance among labs that do blood testing, and how they can legally post results that are significantly different from another certified lab—even on identical samples. But what about supplements and prescriptions?

This week we’ll look at how much you can trust the label on your supplement bottle.

You probably know that in the United States there’s little oversight on the manufacturing and sale of over-the-counter (mail order) supplements. For all practical purposes, a bottle sold as “Vitamin C” could have anywhere from zero to many times the amount or purity claimed. Nobody checks.

As a personal scientist, I don’t particularly want a legally-mandated testing system for supplements. I’d rather make up my own mind, both on the trustworthiness of the manufacturer as well as the makeup and efficacy of the pills themselves. I trust my ability to evaluate the reputation and believability of the seller. Or to put it more precisely, I want the flexibility to put whatever I want into my body, without some “expert” deciding for me what’s okay what’s not. I’m of course happy to listen to what the experts think, but experts disagree on just about everything, so ultimately I’ll need to decide for myself.

Regulation means less innovation

Pharmaceuticals are regulated under laws passed since the 1962 Kefauver-Harris amendments that required efficacy proof (not just safety) before you’re allowed to try a new drug. Your first reaction might be to assume this is a basic requirement of living in a civilized society. After all, without some legal oversight, profit-driven companies have a built-in incentive to overpromise and even cut corners on quality and safety—perhaps at your expense.

That may be a perfectly legitimate attitude for non-scientists who don’t want to be bothered with the messy process of getting at the truth. But personal scientists know that no expert cares as much as you do about something that directly affects you or a loved one.

And those FDA rules come at a cost, a steep one for those of us who want to see more innovation and are willing to trust our own judgement to decide if something works or not.

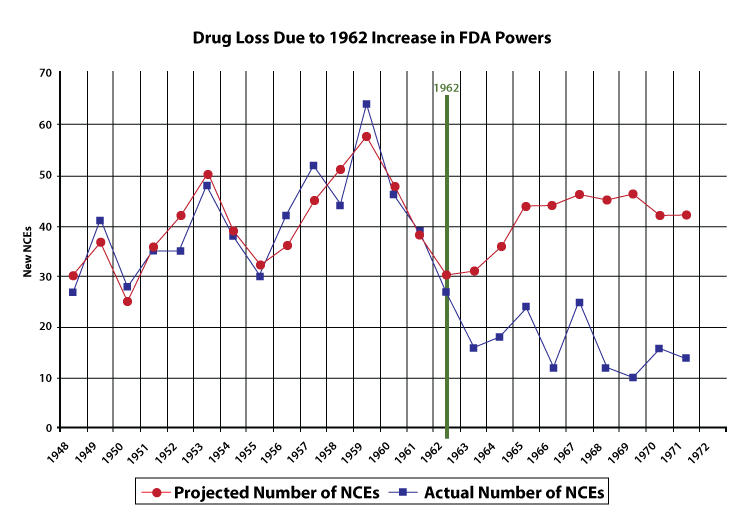

Economist Sam Peltzman studied this rigorously in his landmark 1973 paper. Before 1962, the pharmaceutical industry introduced an average of 40 new chemical entities (NCEs) per year. After the amendments took effect, that number dropped to about 16 per year—a 60% reduction that Peltzman’s statistical model attributes directly to the new regulatory burden. (Paid subscribers know we discussed this in Unpopular Science 240317)

The chart shows Peltzman’s predicted vs. actual NCE introductions. His model, built on pre-1962 data, accurately tracked the market until the amendments hit—then actual introductions diverged sharply downward.

Worse, the new laws didn’t even improve drug quality. Peltzman found that the proportion of ineffective drugs reaching the market remained roughly constant (~10%) before and after 1962. The market was already filtering bad drugs through physician experience, patient outcomes, and liability concerns. The FDA requirements added enormous costs without meaningfully improving the drug pool.

Casey Mulligan’s 2021 NBER update applied this framework to COVID vaccines and estimated that the 48-day delay between Pfizer’s clear efficacy results (November 5, 2020) and Emergency Use Authorization (December 22, 2020) cost 6,000-10,000 additional nursing home deaths. The total economic cost of vaccine delay: roughly $1 trillion.

The FDA faces what Alex Tabarrok calls the “invisible graveyard” problem: when the agency approves a harmful drug, there are identifiable victims, lawsuits, and Congressional hearings. When it delays or blocks a beneficial drug, the victims are statistical—they never knew the treatment existed. This asymmetry creates systematic bias toward excessive caution, regardless of net health outcomes.

None of this means the FDA does no good. But the tradeoffs are real, the costs are larger than commonly acknowledged, and the same logic applies when people propose stricter supplement regulation.

How to tell for yourself

It’s important to remember that “no regulation” is not the same as “no oversight”. Partly because the government doesn’t monopolize the testing of supplements, there is a healthy market of third parties who compete to evaluate supplement quality.

Examine.com is an independent educational organization that claims to have the largest database of nutritional and supplement information on the internet. As we noted back in 2022, Elizabeth Van Nostrand studied their site and concluded that, while the summaries are well-done and extensive, they’re incomplete. “If a particular effect is important to you, you will still need to do your own research,” she concludes. (By the way, Elizabeth’s writing at Aceso Under Glass is a great resource for Personal Science in general, definitely worth following).

The three main independent testing labs are ConsumerLab (consumerlab.com), Labdoor (labdoor.com), and SuppCo (supp.co). I’ve tried them all, but I don’t have any reason to recommend one over the other (see PSWeek250731). But I’d like to know if, as with blood, there are some supplements that are particularly difficult to manufacture consistently.

Evaluating supplement quality

I asked Claude to summarize what ConsumerLab has learned from testing over 7,000 supplements since 1999. The overall failure rate? About 22%—roughly one in four or five products fails to meet quality standards.

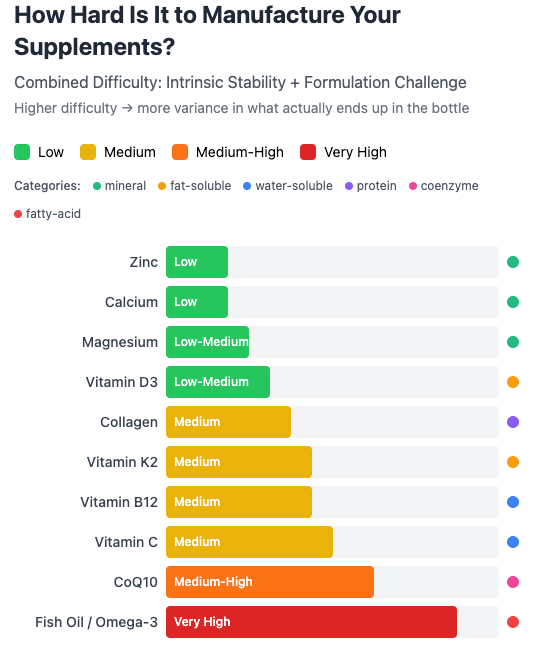

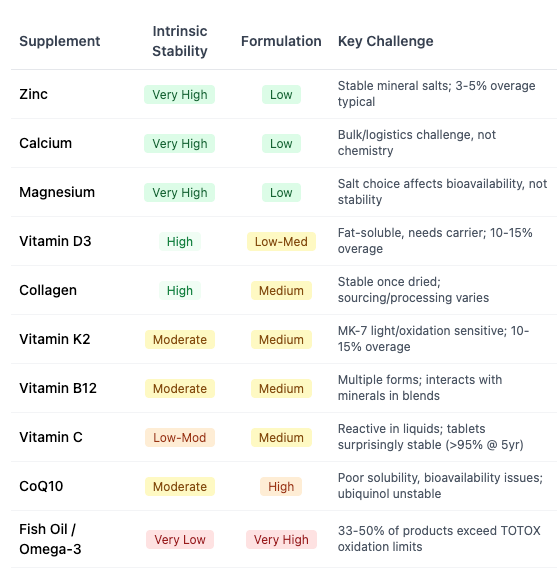

The failure rates vary dramatically by category, but digging deeper I think the answer is obvious. Some “non-chemical entities” are just easier to manufacture and transport than others. Here’s what I got when I double-checked Claude against other facts:

In general, anything that’s a mineral requires little processing (zinc and calcium are basically glorified rock). Something that requires more chemical reactions for processing, or that relies on harvesting biological matter (e.g. fish oil) will be much harder to get right.

Bottom line: choose generic brands for the items at the top of this chart, but carefully consider the independent reviews for the others.

More on pharmaceuticals

Speaking of regulation, although the FDA requires drug manufacturers to submit to all kinds of paperwork before they can sell their products, it can be difficult for normal people to see the details. For example, do you know exactly where your prescription drug was manufactured?

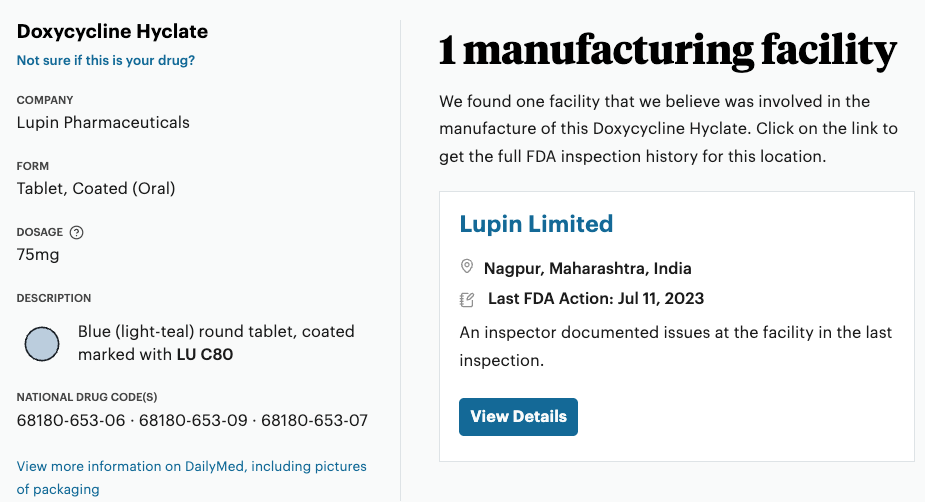

Propublica rx Inspector lets you type in a generic prescription and it will tell you. For example, here’s what it says about the drug I took for Lyme. Click “View Details” and it tells you the FDA notes on each of their inspections.

Personal Science Weekly Reading

Claude keeps getting better and better. Their iPhone app now integrates with Apple Health and I’m now able to ask more intimate questions easily and fluidly. This is a game-changer that I’ll discuss in future posts.

Speaking of Claude, please check out a new app I “vibe-coded”: TextKeep is a simple app for MacOS that lets you save your iPhone text messages as easily-editable files on your computer. For technical reasons, Apple doesn’t allow iMessage apps in the App Store, so you’ll need to download it directly from my site. But it’s a real Mac app, notarized and virus-free. Please check it out and let me know how you like it!

The cool part is how easy it was to build this app: literally less than an hour. My mind is racing over all the other cool apps that are now possible thanks to how easy LLMs have made it to do serious software development.

People Science is running a sleep study to test a new type of probiotics for its effectiveness in people with sleep troubles. Check out their website and application form to see if you quality. You’ll need to take a couple of before/after microbiome tests and take their probiotic for 15 weeks, but if you complete everything they’ll give you an Oura Ring and $100 for your trouble. (You need to have pretty serious insomnia—they didn’t approve some of the sleep-deprived people I know)

About Personal Science

The hard part of personal science isn’t finding information — LLMs have made that almost trivially easy. The hard part is figuring out which ideas are worth your time in the first place. What should you actually track? Which supplement claims deserve a real experiment versus an eye-roll? When does a new study matter for your situation?

That's what we try to do here each Thursday: not rehash what you could ask Claude yourself, but highlight the ideas and tools that a curious, skeptical person might want to follow up on.

Is there something else you think is interesting about supplements? Let us know

I don't think that's necessarily correct as to nutritional supplements not being tested - AFAIK, the FDA does require testing to justify whatever label claim is being made, such as 1000 mg Vitamin C per capsule, as well as maintaining records of such testing and following certain rules related to GMP - Good Manufacturing Practices.

On an actual OTC drug product, such as an antacid, I can verify there are extraordinarily strict FDA requirements in place - we were audited by the FDA at the Tums plant in St. Louis last year. It lasted the better part of a week, and I was impressed by how thorough the audit was despite being led by a newer auditor still in the process of being certified by the agency. We did extremely well, which I didn't find surprising - I've never worked anywhere as focused on quality as the Tums site is.

On Tums, we do laboratory testing to verify the label claim (either 500 mg, 750 mg, or 1000 mg of calcium carbonate per Tums tablet), as well as the corresponding acid neutralization capacity at each strength. Part of my job is reviewing that testing data. An outsider would be dumbfounded at the strictness of the rules we have to follow even though it's just an OTC drug. I worked once at another pharma company making much higher tech products, and it was very much the same environment.

On the supplements mentioned, I'm very much familiar with the omega-3 situation - these fatty acids have multiple double bonds and are extremely susceptible to damage in the manufacturing process. I used to buy cheap fish or flaxseed oil at Target, but with all the reading I've done, I no longer do. Currently, I'm using what appear to be carefully made flaxseed oil capsules (containing alpha-linolenic acid, an 18-carbon omega-3 with three double bonds), and fish oil capsules (containing eicosapentaenoic acid [EPA] - an omega-3 with 20 carbons and five double bonds, and docosahexaenoic acid [DHA] - an omega-3 with 22 carbons and six double bonds).

It states on the flaxseed oil label that the product is made from organic flax seed oil that is cold-pressed and unrefined. Those processing conditions will greatly protect the double bonds if true. I'm inclined to believe the label information is correct because the liquid itself in the capsules is a dark reddish brown, indicating to me that is unrefined. This product would be totally unsuitable as a cooking oil because of certain molecules that have not been removed and would exhibit undesirable characteristics when heated. Refining cooking oils is usually a complicated industrial process intended to remove molecules negatively affecting cooking performance. They are usually light in color at the end of the process but can suffer double bond damage from all that processing, as well as potential UV damage from typically being sold in clear plastic bottles.

The oil in the fish oil capsules I have go through a molecular disassembly and reassembly process at the manufacturer, mainly to improve purity and increase EPA and DHA content, I gather. While expensive and ostensibly high quality, I actually have more confidence in the quality of the flaxseed oil because it's less apparent to me what processing conditions were actually used in manufacturing the fish oil. If I have all the necessary micronutrients in my body and everything is working optimally, I should be able to turn the alpha-linolenic acid in the flaxseed oil myself into the two special oils contained in the fish oil, which are extremely important for good health. But I'm not positive I can actually do that, hence my use of this fish oil product.