Personal Science Week - 260122 Trends

Multiple lab results are better than one

Personal scientists love to track biomarkers over time, watching for changes that might signal a need to adjust diet, supplements, or lifestyle. But here’s something professionals know but rarely acknowledge: the precision we assume in lab results simply isn’t there.

This week we’ll explore the surprisingly wide allowable error margins in standard blood tests, and what this means for those of us who track trends.

Back in PSWeek250904 we mentioned the best deal in blood testing: as low as $142 for a comprehensive 100+ biomarker lab draw available through SiPhox and LabCorp. That offer is unfortunately no longer available—SiPhox has since decided to focus exclusively on at-home tests—but hopefully some of you, like me, got yours in time.

As long-time readers know, I’ve done regular at-home blood testing with SiPhox (PSWeek221117), phlebotomist-drawn tests from LabCorp (PSWeek240125) and Quest, a whole series with Function Health (PSWeek240912), and various at-home cholesterol tests (PSWeek250213).

But how much can I trust these results?

The CLIA Reality Check

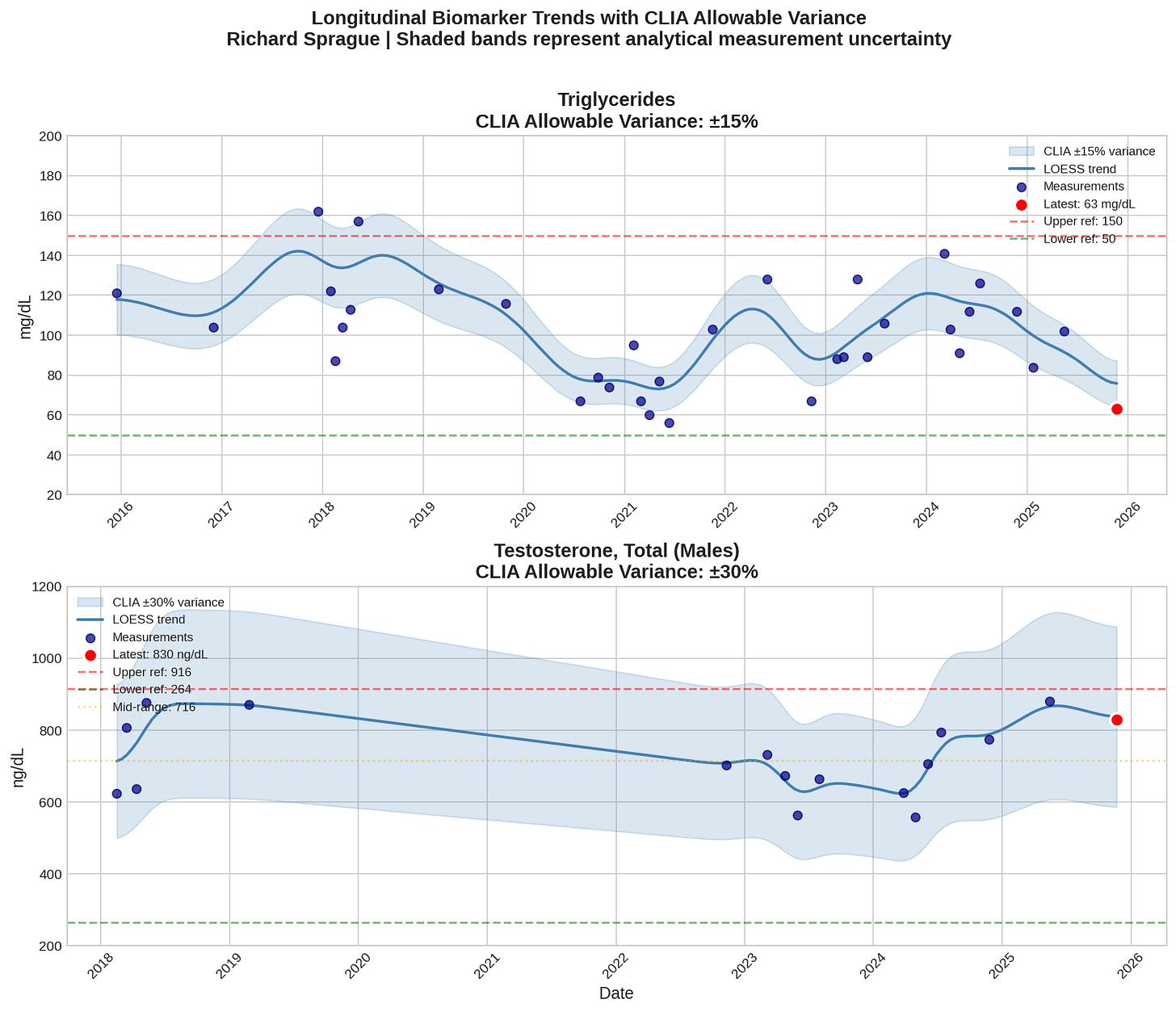

My new lab report says my testosterone is 830 ng/dL and my triglycerides are triglycerides of 63 mg/dL. Both are considered excellent numbers for my age, but there’s a huge caveat: I must assume the values are accurate. That seems reasonable: after all, these results come from regulated medical laboratories using sophisticated equipment.

But the federal regulations governing lab accuracy are far more permissive than you’d expect.

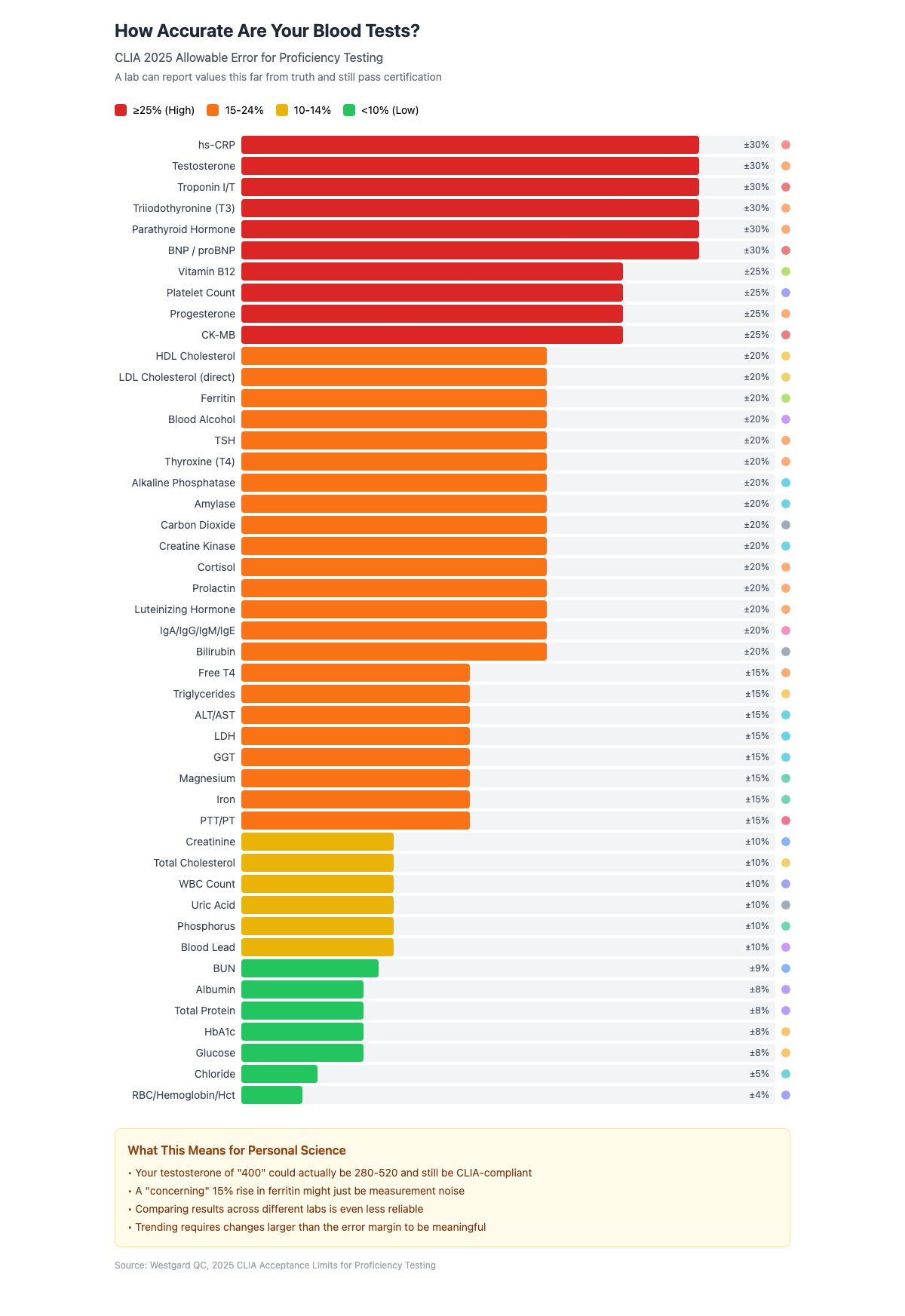

The Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) set the standards US labs must meet. This table from Westgard QC shows allowable variance for proficiency testing that took effect January 1, 2025:

If my testosterone had been slightly lower, say 400 ng/dL, the actual value could be anywhere from 280-520 and the lab would still be CLIA-compliant. That’s a range spanning “clinically low” to “perfectly normal.”

How many people come back from a single blood test thinking either (1) everything’s great, or (2) I’m in trouble — when the real issue is simple testing error!

Lab vs Lab

The situation gets messier when you compare results from different labs.

As we noted in PSWeek231109, different labs can legally report wildly different values while still being CLIA-compliant. Vitamin D is notoriously variable: one lab might report 30 ng/mL while another reports 50 ng/mL for the same blood sample. The main criterion for certification is consistency within the same lab, not measurement against an objective external standard.

So if you switch from SiPhox to Function Health, or from Quest to LabCorp, you can’t compare the numbers directly. Your carefully maintained spreadsheet essentially starts over.

Actionable Thresholds

Doctors make treatment decisions based on cutoffs. Statins, testosterone replacement, thyroid medication—these are all prescribed based on specific levels.

But if that LDL measurement could legitimately be 135 or 165 (with a reported value of 150), you might be on either side of a treatment threshold purely due to assay variance.

Worse, this variability applies to research labs too. If a peer-reviewed study makes a health claim based on Vitamin D levels under 30 ng/mL being “low,” you can’t compare your own results unless you know precisely which lab did the analysis.

In fact, this high variability has me questioning the entire premise of Vitamin D supplementation. (see PSWeek251210)

The Trend is Your Friend

The solution is that you need to track biomarkers over time rather than obsess over single values.

Use the same lab, consistently. Different labs may give systematically different results. Stick with one provider to maximize comparability.

Don’t panic over small changes. A 15-20% change in most biomarkers is within the noise floor. Look for large, persistent trends.

Establish a baseline range. Consider 2-3 measurements under similar conditions before attributing changes to interventions.

Know which tests are precise. Glucose, HbA1c, and hematology values are reliable. Hormone tests and inflammatory markers are not.

Focus on effect sizes that matter. Design experiments with interventions likely to produce big effects—or accept you’re collecting hypothesis-generating data, not definitive proof.

And finally, compare yourself to yourself, which is often more informative than comparing to population averages. (see PSWeek240509)

Here’s what happens when I asked Claude to regenerate my data using the error bands that my labs should have put there.

My actual results are somewhere in those shaded bands and in this case, you can tell that I was doing some kind of intervention in the top chart, where the triglycerides go up and down, versus the bottom chart where my overall levels are essentially unchanged.

Personal Science Weekly Readings

Speaking of how to get better results from imperfect data, What If Everyone Knew Which Science to Trust? by Paul Litvak introduces a new project to create AI tools that will systemically go through academic papers and “peer review” them according to the rigorous unbiased standards that only an AI can do.

evidence.guide hosts an API that turns a PDF into structured (JSON) data with fields like p-value, number of experiments, etc. making it easier to automatically compare studies.

refine.ink is a $50 site that “devotes hours of compute to help you find and fix the issues that matter most to readers and reviewers.”

Speaking of bad research, I was intrigued by a new paper that was summarized by Eric Topol as “Multilingualism and Extending Healthspan”. The idea is exciting: learning another language makes you live three years longer! The paper is based on an analysis of almost 90K people in Europe, which sounds impressive until you see their methods. Their definition of “multilingual” is basically self-reported, so people who studied Spanish in high school could count.

Smithsonian compiles its list of Ten Celestial Events for 2026 including a lunar eclipse on March 3rd and a solar eclipse partially visible in Alaska, Canada, and the Northeastern US on August 12

About Personal Science

Personal scientists use the tools and methods of science for personal rather than professional reasons. That includes understanding the limitations of those tools, not just their capabilities.

Lab tests are powerful instruments, but they’re noisier than most people realize. The confidence doctors express about precise numbers (”your B12 is 412”) is often epistemically unjustified. Knowing this doesn’t mean we should stop testing—it means we should interpret results with appropriate humility.

We publish this newsletter each Thursday for anyone who prefers thinking for themselves. If you have other topics you’d like to discuss, please let us know.

So helpful! Thx!!

Brilliat breakdown of CLIA variance limits. The threshold problem is especially concerning when treatment decisions hinge on values that could swing 25% either way just from measurement error. I switched from Quest to LabCorp last year and my vitamin D dropped 15 points, which had me worried until I realized it was probaly just lab calibration differences. Tracking trends within onelaboratory makes so much more sense now.