Personal Science Week - 251210 Attention

Maybe just paying attention is what counts

Personal scientists care about the material, empirical world of biomarkers and experiments, but we recognize the limitations.

This week we’ll step back and think about the what science can do, and what it can’t.

The Naturopath’s Wall

Back in PSWeek250213 I mentioned that I share my mother’s lifelong high blood cholesterol, and how her sudden need for a stent operation early this year has me digging further into family medical history. So recently I joined my father on his annual medical visit, this time to a well-regarded naturopathic doctor as he reviewed Dad’s latest blood test results. I wanted to know how his advice would differ from an LLM, so I gave ChatGPT the same panel that the doctor was reviewing and received a detailed answer concluding all is well except for some borderline kidney function (eGFR), which was out of line for his age.

The doctor saw something different. Barely glancing at the eGFR, he was concerned instead about the “low” vitamin D level of 37 ng/mL (which most reference ranges say is just fine). That was the only number he needed to launch into his theory about inflammation, cholesterol irrelevance (”taking a statin is like shutting off the water to the whole house because of a leak”), and the necessity of taking Vitamin D and K2 together.

How is this doctor’s single-minded focus on Vitamin D any different from my cardiologist’s focus on blood cholesterol? Both of them treat a single blood parameter as if it’s the most important predictor of health.

On the wall hung a framed magazine profile of the doctor, from 2002, back when he was much younger. I found myself wondering: what was he prescribing twenty-five years ago. Probably not the vitamin D + K2 protocol—that wasn’t fashionable yet. Maybe antioxidants? Fish oil? The specific molecule rotates with the decades; but the doctor’s confidence remains constant.

Values in Science

Here’s the uncomfortable truth that philosophers of science have been pointing out for decades: science is not value-free. What questions we ask, what counts as “significant,” what we consider adequate evidence—all shaped by values. The naturopath and the cardiologist aren’t just interpreting the same data differently; they’re asking different questions entirely.

The cardiologist asks: “What interventions reduce mortality in large populations?” The naturopath asks: “What underlying imbalances might be causing symptoms?” These aren’t the same question, and the same blood panel won’t answer both.

This sounds like a problem. If science can’t give us neutral, value-free truth, what good is it?

But for personal scientists, this is actually liberating. We don’t have to pretend we’re doing view-from-nowhere objective research. We can be explicit: I care about my own health, my own energy levels, my own longevity. That’s the value that drives us. Unlike the professional researcher who must obscure their motivations behind grant applications and publication pressure, we can name what we’re after.

The medical professionals mistake isn’t having values. It’s not being explicit about them—and not being honest about the limits of his experience.

Escaping Nihilism

So if “science” and experts disagree, and even peer-reviewed studies fail to replicate—where does that leave us? Some people land on nihilism: nothing is knowable, believe whatever feels right. Instead, here are my favorite ways to deal with uncertainty:

The Lindy Principle: Things that have survived a long time will probably survive longer. Olive oil, fermented vegetables, walking, sleep—these have passed through the filter of centuries. By contrast, Vitamin D and statins have only decades of proponents. And don’t get me started on Rapamycin or NAD.

Chesterton’s Fence: Before you tear down a fence, understand why it was built. Before you reject religious fasting as superstition, notice it’s been Lindy-tested for millennia.

Skin in the Game: Grandmother’s heuristics beat nutritionist’s models because grandmothers had skin in the game across generations. The practices that killed people got selected out.

Or maybe the active ingredient is attention itself. Kosher laws, Ayurvedic doshas, macro counting, carnivore, vegan—wildly different content, often similar outcomes for adherents. What do they share? A framework that makes you think about what you put in your body. You’re not on autopilot.

The naturopath’s vitamin D fixation, the cardiologist’s cholesterol obsession, the biohacker’s supplement stack—perhaps they all “work” partly because they force structured attention to health. The specific theory matters less than having a theory that keeps you engaged.

The real question isn’t which evidence to trust. It’s whether your framework—whatever it is—keeps you paying attention.

Personal Science Weekly Readings

Speaking of Vitamin D, here’s your regular reminder that different testing companies can report very different values while still being compliant with regulations. See PSWeek231109 for examples of how different labs can legally report wildly different levels of Vitamin D (30 ng/mL vs 50) because the main criteria for certification is consistency within the same lab, rather than measurement against an objective standard.

Scott Alexander’s December Astral Star Codex links describes why the popular genetic testing company Nucleus might not be as quality as they claim.

So which genetic test should you get? These days, I’d just ask my favorite LLM but you can get a (slightly old) summary of what’s involved with geneticist Razib Khan’s 2022 So you want to test your DNA.

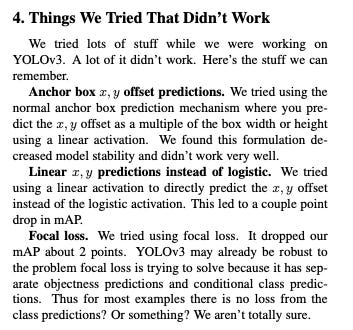

I wish every academic paper included a section like this one

I want to hear the case for why Hepatitis B vaccines should be given to infants. Unless the mother is in a high-risk group (e.g. drug user), I just don’t understand why this would be mandatory for the millions of babies born each year. The best, most recent “pro case” seems to be Hepatitis B Vaccination: A Remarkable Success Story That Must Continue but this fact-check makes me wonder how that made it through peer review or how a responsible doctor would recommend it for everyone.

Speaking of misrepresenting the truth, a recent NPR headline should have you outraged at government cuts in science, until you hear that the “researcher” is a 76-year-old PI who hasn’t done anything original in years and basically operates a factory for cheap labor from post-docs who slave away at boring unpromising tasks.

About Personal Science

Personal scientists prefer to figure things out for ourselves. We listen to experts not because they’re necessarily right, but because they’ve had more experience than the rest of us. Still, experts are often wrong and frequently disagree with one another, so whether you listen to experts or not, you’ll need to make up your own mind.

The philosophy of science reminds us that “science” isn’t a magic oracle delivering truth. It’s a set of methods—useful ones—with real limitations. Understanding those limitations doesn’t undermine personal science. It clarifies what we’re actually doing: making bets under uncertainty, tracking what works for us, and staying revisable when the evidence shifts.

Nullius in verba—take no one’s word for it. Including mine.

If you have other topics you’d like to discuss, please let us know.

I liked the references to Taleb’s framework ideas. He has some interesting ideas about health…

Don't know anything about this particular case, but doesn't "PI who hasn’t done anything original in years and basically operates a factory for cheap labor from post-docs" pretty much describe how research works? 😅