Personal Science Week - 251225 Christianity

Merry Christmas, seriously

Nothing could be more unscientific than religion. At least, that seems to be the mainstream view among professionals.

Personal scientists are allowed to think a little more open-mindedly, so in honor of Christmas, this week we’ll make the case for why it’s okay to be a believing Christian and still remain true to science.

The History of Science and Religion

Virtually all great thinkers we associate with Scientific Revolution and well into the Industrial Age (Descartes, Galileo, Newton, Maxwell, Mendel) were practicing Christians, as sincere in their religious beliefs as they were in their professional work. In fact, many of them considered their scientific inquiries to be a direct consequence of their theological ones. When the Protestant Reformation exposed different interpretations of traditional beliefs about scripture, many thinkers turned to the natural world of God’s Creation as a way to read additional clues that could settle theological arguments. A personal God who made us in His Image surely must have designed His Creation in a way that will afford answers to those who seek diligently.

Contrast this with

Islamic occasionalism: God directly causes every event; no “laws of nature” to discover

Greek/Chinese cyclical cosmos: everything repeats; no concept of progress or discovery

Animist worldviews: nature is populated by capricious spirits, not governed by laws

Of course, after Darwin the picture became more complicated, but it’s important to remember Darwin himself was immersed in a Christian world. His alma mater, University of Cambridge, required all students to take an Oath of Supremacy; ability to read and comment on the Gospels (in Greek!) was a requirement for graduation. He almost certainly knew more about the Bible and Christianity than you do!

You may know that in the US all the top Universities began as divinity schools, but did you know that well into the 19th and 20th centuries they required all students to attend chapel on Sundays? Harvard ended compulsory daily prayers in 1886, but Yale didn’t follow until the 1920s. Brown and Princeton were among the last Ivies to require chapel: Brown ended compulsory chapel in 1959 and Princeton phased out the last mandatory Sunday services by 1964.

In other words, whatever the personal beliefs (or anti-beliefs) of most important scientists until well into living memory, they all had significant Christian exposure.

On the other hand

Modern science would be incomplete without the Enlightenment, many of whose key thinkers famously positioned religion (especially Christianity) as outdated and even harmful: Voltaire, Hume, Gibbons, Thomas Paine. Even those who weren’t explicitly anti-religious were comfortably secular, hiding behind “Deism” (God might exist but he doesn’t interact with the world) or what today we’d call agnosticism. Thomas Jefferson, for example, was able to write about rights “endowed by their Creator” in the Declaration of Independence, but downplayed any specifics.

Many, perhaps most modern thinkers go further. If you’re up-to-date on popular science, you’ll have no trouble rattling off all the reasons why religion is bad. For some people the term itself is a synonym for “superstition”, with additional suspicions thrown in: **bigotry, oppression, closed-mindedness.

But I wonder how much of this is a generations-long reaction to the overwhelming hold that Christianity had on everything in western society.

Aaron Renn describes Christianity in America as proceeding in three phases over the past fifty years. Until the 1990s, it was a positive, where public officials needed to pay homage to their Christian beliefs whether or not they were sincere. By the early 2000s, perhaps in reaction to the George W. Bush presidency as well as the perceived excesses of the Moral Majority years, American elites shifted to Christianity as a neutral force. It’s fine if you’re Christian, fine if you’re not. By the 2010s and especially after the rise of Trump, Christianity is seen as a negative. Self-respecting elites gain prestige by being actively anti-Christian.

I wonder if the same thing happened in Academia a generation or two ago before this wider political shift.

Compared to what?

Early 20th century Progressives, animated by Darwin’s theories of Natural Selection, were proud to use the language of science to reject many long-standing Christian principles, including the fundamental dignity of every human being. By actively rejecting religion as “anti-science”, eugenics must have seemed a natural consequence of their reason-based, scientific approach to crafting a better society.

Go down the list of your favorite Progressive forbearers: Jane Addams, Irving Fisher, David Starr Jordan, Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, John Maynard Keynes, all the founders of American economics (and today’s prestigious AEA), sociology, and revered legal scholars like Oliver Wendell Holmes. Every one of them was a proud eugenicist — and proud that they were fighting the Catholic Church, which condemned eugenics from the start.

The scientists who developed the birth control pill didn’t care that they were violating long-standing Catholic teaching against contraception; their first clinical trial was conducted on unsuspecting poor Puerto Rican women. One of the only groups to publicly oppose the Japanese internment in WW2 was the Baptist Church, whose missionaries were the few white Americans with direct interaction with them.

In a world plagued with scientific fraud, would it be a bad thing to live in a society where everyone attends a one-hour lecture on morality and ethics each Sunday?

Personal Science Weekly Readings

Speaking of religion, see PSWeek241017 where we wrote about our visit to a Creationist Theme Park. Paid Subscribers can also read our Unpopular Science posts for even more controversial takes on science and religion.

This is a good week to read books, so here are a few to consider:

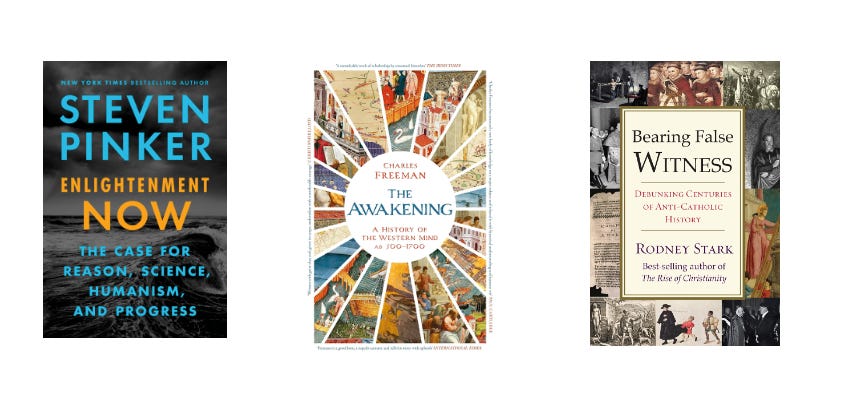

Steven Pinker’s Enlightenment Now is the definitive case for why science and religion should have nothing to do with one another. Although I’ve been one of his biggest fans since his first book The Language Instinct and The Blank Slate, I thought this book was poorly argued, misrepresenting Nietzsche for example and ignoring the much Bad Stuff done in the name of the Enlightenment (e.g. French Revolution, Communism, Fascism)

Charles Freeman The Awakening is a textbook-level look at the role Christianity played in both the decline of the Greco-Roman world and later in what he calls “The Reopening of the Western Mind”. He argues convincingly that many of the early scientific thinkers were less influenced by Christianity than many scholars claim.

Rodney Stark is a sociologist who debunks many of the common stories you’ll hear about historical Christianity. Bearing False Witness: Debunking Centuries of Anti-Catholic History warns that many of our history narratives are passed down from 16th century (Protestant) European countries who were at war with (Catholic) Spain-Italy-France and tended to embellish stories about Galileo vs. the Church (the Church was fine with heliocentrism but after the Reformation they weren’t fine with Galileo’s politics) or the Inquisition (which had fewer actual executions for heresy than Britain at the time).

“There are not one hundred people in the United States who hate The Catholic Church, but there are millions who hate what they wrongly perceive the Catholic Church to be.”

- Fulton Sheen

Merry Christmas

There are other religions, of course. You’ve probably attended a scientific meeting that began with a word of prayer land acknowledgement or reading from Holy Scripture a code of conduct. But today, of all days, it should be okay to post about the one religion that has undeniably had the closest connection to science of all.

Good personal scientists are skeptical about everything, and of course all religions—including Christianity—are a rich target. But it’s important to be humble about what we don’t know. Remember that people way smarter than you have struggled with every possible scientific objection and many of them came away as firm believers.

You don’t have to be a Christian to be a good scientist, but you don’t have to be anti-Christian either.

About Personal Science

If you studied science in college and grad school, you might now work as a professional scientist, planning and executing experiments, publishing papers and attending conferences. That’s your job.

Personal scientists use the same tools and ideas as the professionals, but we turn science back at topics of direct interest to our daily lives.

We publish every Thursday. If you have other topics you’d like to discuss, please let us know.

Love this! Merry, merry!!

There are many famous scientists who were/are practicing Christians, though usually from a grown-up denomination like Catholicism, rather than a sect that requires believing that Earth is 6,000 years old. Or they're just very good at compartmentalizing...