Personal Science Week - 250529 Travel

How important is travel for personal science?

I’m back from short visit to Rome, Italy. Between viewing the ancient ruins and sampling the fresh pasta, how did I change?

This week we’ll review some of the ways travel affects us, and some of the ways it doesn’t.

Measuring International Travel

I’ve done extensive self-testing on international trips in the past. Wearables, like an Apple Watch or a CGM make it easy to accumulate quantitative data about the physical effects of travel. But I’ve never found anything super-interesting that way. Jet lag affects my sleep! I walk more when I’m in an historic city center without cars! Not exactly Nobel prize-worthy insights.

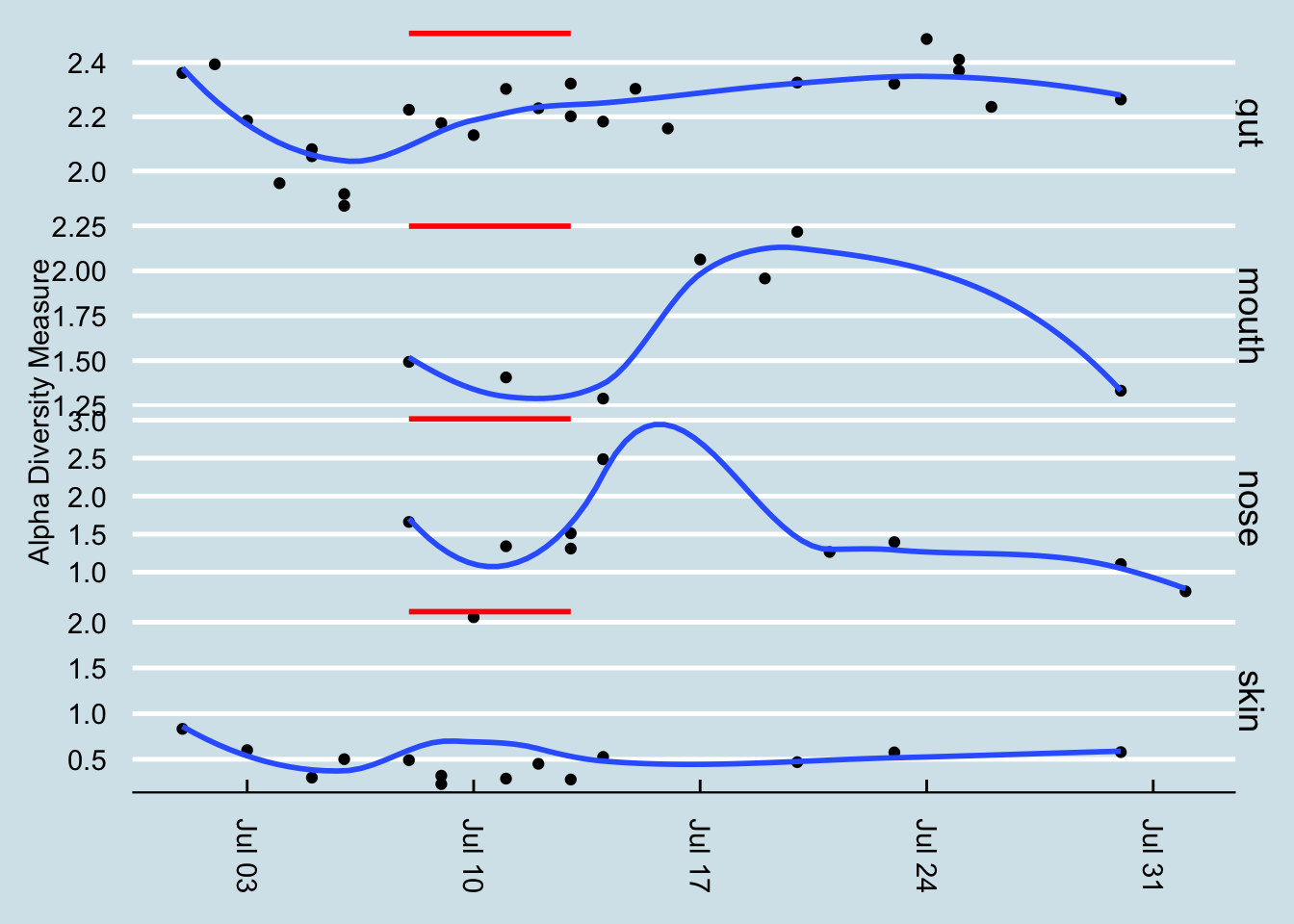

For example, on a trip to China several years ago, the most notable change happened after I returned home: I saw a clear increase in Pseudomonadota (also known as proteobacteria) in my gut, along with a slight uptick in microbiome diversity (Shannon index). Importantly, these changes didn't occur during travel itself, but in the days following my return.

It’s interesting that the changes appear mostly after the trip, but the timing makes sense when you think about it. During travel, you're exposed to new environments, different foods, varying sleep schedules, and travel stress. Your microbiome is remarkably resilient, but it takes time for these accumulated changes to manifest in measurable ways. Despite changes or perturbations to the microbiota caused by factors like diet, antibiotics, illness, or travel, the microbiota has the capacity to bounce back and re-establish its previous, balanced composition and function.

In fact, maybe this is true of other changes we experience from travel. Rather than the trip itself, maybe we change more after the trip.

Does Travel Really “Open the Mind”?

Personal scientists care about open-mindedness. We often hear that travel "broadens the mind" or creates more tolerant, globally-minded citizens. So how important is travel to personal science?

Travel exposes you to different, often non-obvious ways to do things, and in that sense it obviously tends to promote new ideas, at least if you’re paying attention. For example, I noticed that the caps on plastic water bottles in Rome are tethered, presumably to lessen the trash that comes from loose items. Now why didn’t we think of that in the US?

That’s just one tiny example, but it hints at the wealth of new perspectives you gain with exposure to other cultures. That’s why recent policy changes restricting foreign student visas seem like a bad idea, not just to the foreign students themselves (who lose access to great American universities) but to their fellow students (who won’t benefit from exposure to the diversity of cultures that results).

But personal scientists are open-minded and skeptical. There’s often a difference between what we expect in theory and what happens in the real world. What does the actual data show about whether exposure to other cultures creates meaningful connections?

The reality is more sobering. 85% of Chinese international students say they don't have a single American friend, and 40% of foreign students in the US have no close friends on campus. For all the potential diversity you’d think a university can offer by bringing in foreign students, the sad truth is that many—most—of those students continue to interact only with each other. That's not exactly the intercultural bridge-building we'd expect if proximity is all it takes to open your mind.

Even more counterintuitively, a careful analysis by a cross-cultural team from Columbia University found that across eight separate studies, people who spend more time traveling in foreign countries actually show small decreases in moral behavior. The effect sizes were modest but consistent—suggesting that breadth of travel exposure might make people more willing to bend rules or ethical standards.

Interestingly, people who have depth experiences (living in a country for a long time) show less of this effect than those who have breadth experiences (visiting many places briefly).

In other words, physical travel and cultural exposure alone aren't sufficient for meaningful cross-cultural connection. Just as my microbiome changes were most apparent after returning home, perhaps the real "mind-opening" effects of travel require deliberate integration and reflection, not just passive exposure to novelty.

Personal Science Weekly Readings

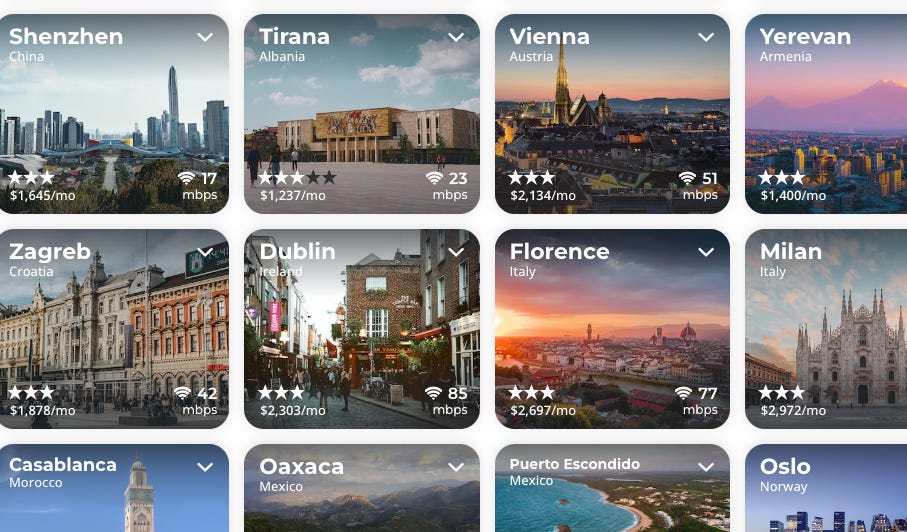

If you want to go in-depth in a country, the best way is to move there. WeNomad is a no-paywall site that ranks countries with all the details you’ll need if you want to become a remote worker.

And if you’re wondering which country is best for you, US News has a short quiz that asks various questions about what values you think are important for a country. When I fill it all in, this is what I get:

Finally, if you think travel is the best way to open your mind, ask yourself if you’re traveling or merely being a tourist.

Philosopher Agnes Collard writes in (New Yorker Jun 2023) The Case Against Travel (archive) that "‘Tourism’ is what we call travelling when other people are doing it."

Even Socrates, in his “Moral Letters to Lucillius” downplayed the role of travel in actually making a change. As illustrator-blogger Lawrence Yeo puts it in Travel is no Cure for the Mind:

Shifting and swapping the contents of your box may briefly alter the shape of it in the form of excitement, but in the end, these things will become just another part of normal life.

And then you realize, aha!, that the problem is that you're trapped into a box of everyday life, and the solution is: escape—through travel!

But here’s the thing. Regardless of what you do to break out of the box, it won’t work. You can change your external environment all you want, but you will continue to travel with the one box that will always accompany you.

About Personal Science

Personal scientists think for themselves, approaching health and life decisions with open-minded skepticism. We collect our own data when possible, remain curious about biological mechanisms, and remember that averages don't define individuals—your travel response might be completely different from mine, and that's exactly what makes personal science valuable.

We publish each Thursday for anyone interested in applying scientific thinking to everyday life. If you have questions, experiences to share, or topics you'd like us to explore, please let us know.

If you travel somewhat regularly, there is a lot you can learn about how you deal with jetlag. For example, I have much less trouble adapting when travelling east (contrary to conventional wisdom). And I know how sunrise and sunset times at my destination are going to affect my recovery time.