Personal Science Week - 260129 Fermentation

Grow your own microbes

A modestly-equipped kitchen is a perfectly good laboratory for any personal scientist. And within the kitchen, fermentation is the ideal starting point: controllable variables, observable outcomes, low stakes, quick feedback, and techniques that humans have refined over thousands of years.

This week we’ll explore what makes fermentation so well-suited to personal experimentation, share some surprising new research about geography and microbes, and review my own experiments with sourdough, koji, sauerkraut, and kefir.

About Fermentation

Part of my interest in home fermentation comes from a friend whose chronic gut problems seemed to stabilize after drinking kefir, the yogurt-type drink you can buy anywhere these days. When he got tired of paying $3/day for the store-bought kind, he switched to making it at home and discovered a whole new level of healing: his gut responded dramatically better with the homemade kind compared to the commercial ones.

This anecdote made me start thinking of fermentation—and microbes in general—as an “external digestive system” that mediates between food in your immediate environment and the delicate process your stomach uses to make it useful for your body. Just like humans use fire to chemically transform food into easier nutrition, fermentation is how we use microbes to do something similar.

Sauerkraut

Last week I finally set up the traditional Chinese-style fermentation jar I received at Christmas. My first project was a simple fermented cabbage (aka sauerkraut). If you’ve not done this before, you’re missing out! It’s incredibly simple: shake a little salt on some shredded cabbage pounded briefly to expose the juices. Stuff it into a container and wait a week.

Sure enough, I now have maybe a gallon of fresh and crunchy sauerkraut.

The lactobacillus bacteria already on the cabbage do all the work. Salt concentration (around 2%) and temperature (room temp is fine) are the only variables that matter.

Sauerkraut is the perfect “minimum viable fermentation experiment”—if you can’t make sauerkraut, you’re overthinking fermentation.

Sourdough

I’ve written about my sourdough bread experiments in PSWeek250911 but here’s the short version: making sourdough from scratch is trivially simple. You literally just mix flour with water and let it sit at room temperature for about a week, “feeding” it daily by discarding half and replacing with fresh flour and water. I’ve continued to experiment several times a week, making sourdough bread whenever I travel and have access to a kitchen.

My “external digestive system” idea matches what people think of as terroir—the idea that San Francisco sourdough tastes different because of unique local wild yeasts. Unfortunately for my theory, a landmark 2021 study in eLife analyzed 500 sourdough starters from four continents and found something surprising: geography doesn’t matter. The researchers concluded that “in sharp contrast with widespread assumptions, we found little evidence for biogeographic patterns in starter communities.” Sorry, San Francisco.

What does predict your sourdough’s character? How you maintain it—feeding schedule, hydration ratio, flour type, and the microbial interactions within the starter itself. The study also highlighted acetic acid bacteria, previously overlooked, as key drivers of aroma and rise rate. Starters with more AAB produce stronger vinegar aromas and slower rises

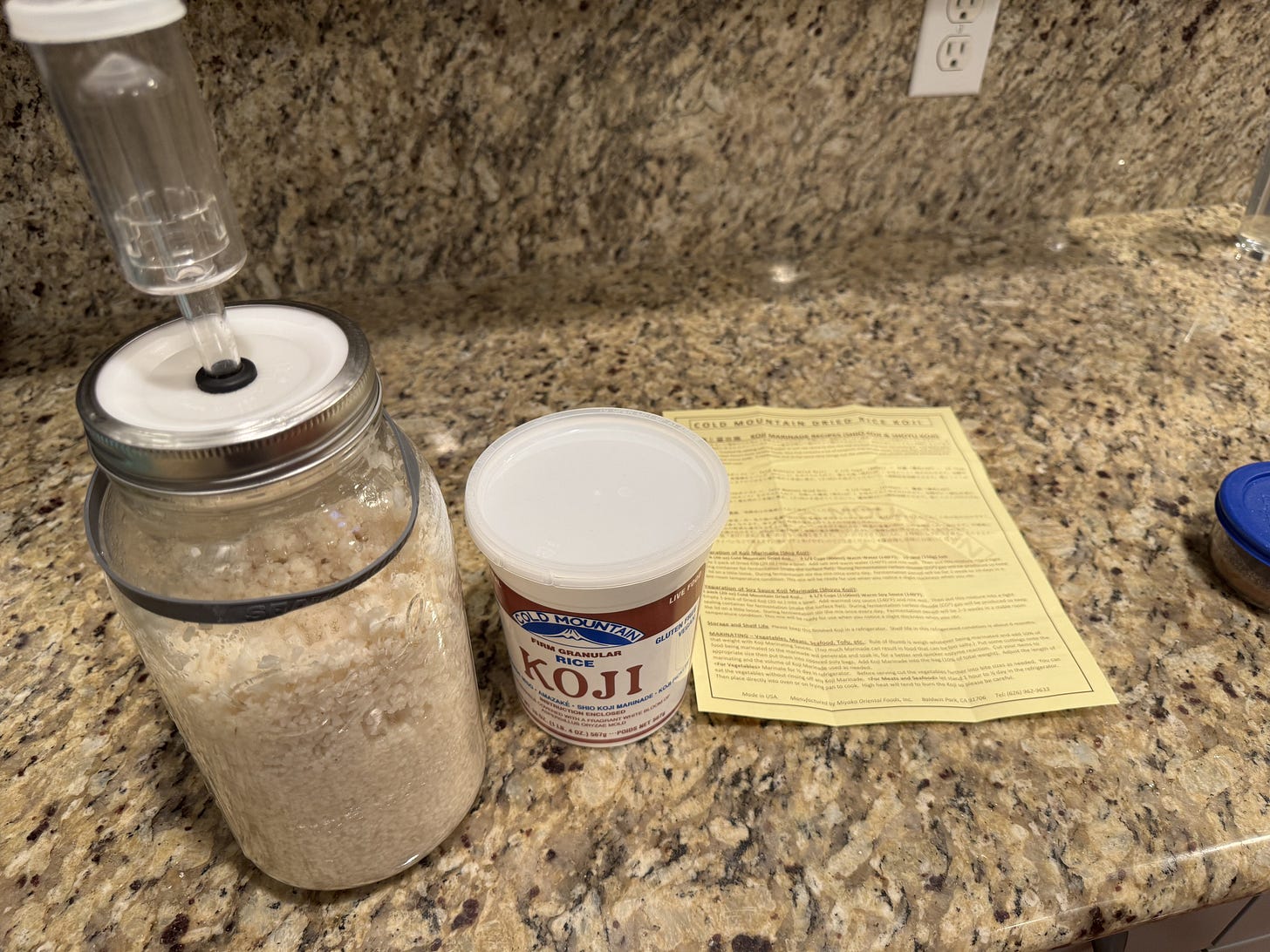

Koji

Another fermentation experiment I’ve been trying is with a Japanese traditional marinade flavoring called koji. It technically isn’t fermentation—it’s Aspergillus oryzae mold growing on rice grains, producing enzymes that break down proteins and starches. When you apply the resulting enzymes for a couple hours (or overnight) to something like chicken or beef, the food takes on a notably softer and sweeter flavor.

To make the marinade, you need to buy koji grains. I bought a one-pound container of Cold Mountain grains for about $10, but you can buy similar brands through Amazon. It looks like ordinary rice, but you mix it with water and salt (4.5% salinity), stirring daily for a week until it tastes both salty and sweet—that’s how you know it’s ready.

I’ve been using it on chicken thighs, cooked sous vide at 148°F for about five hours. The result is noticeably more tender and flavorful than unmarinated chicken. Unlike microbiome changes (which require expensive lab tests to verify), koji success is immediately obvious to your taste buds.

Kefir and Kombucha

The ferments above are all about transforming food. But one of my favorite personal science experiments happened a few years ago when I tried to directly measure the effects on my gut microbiome.

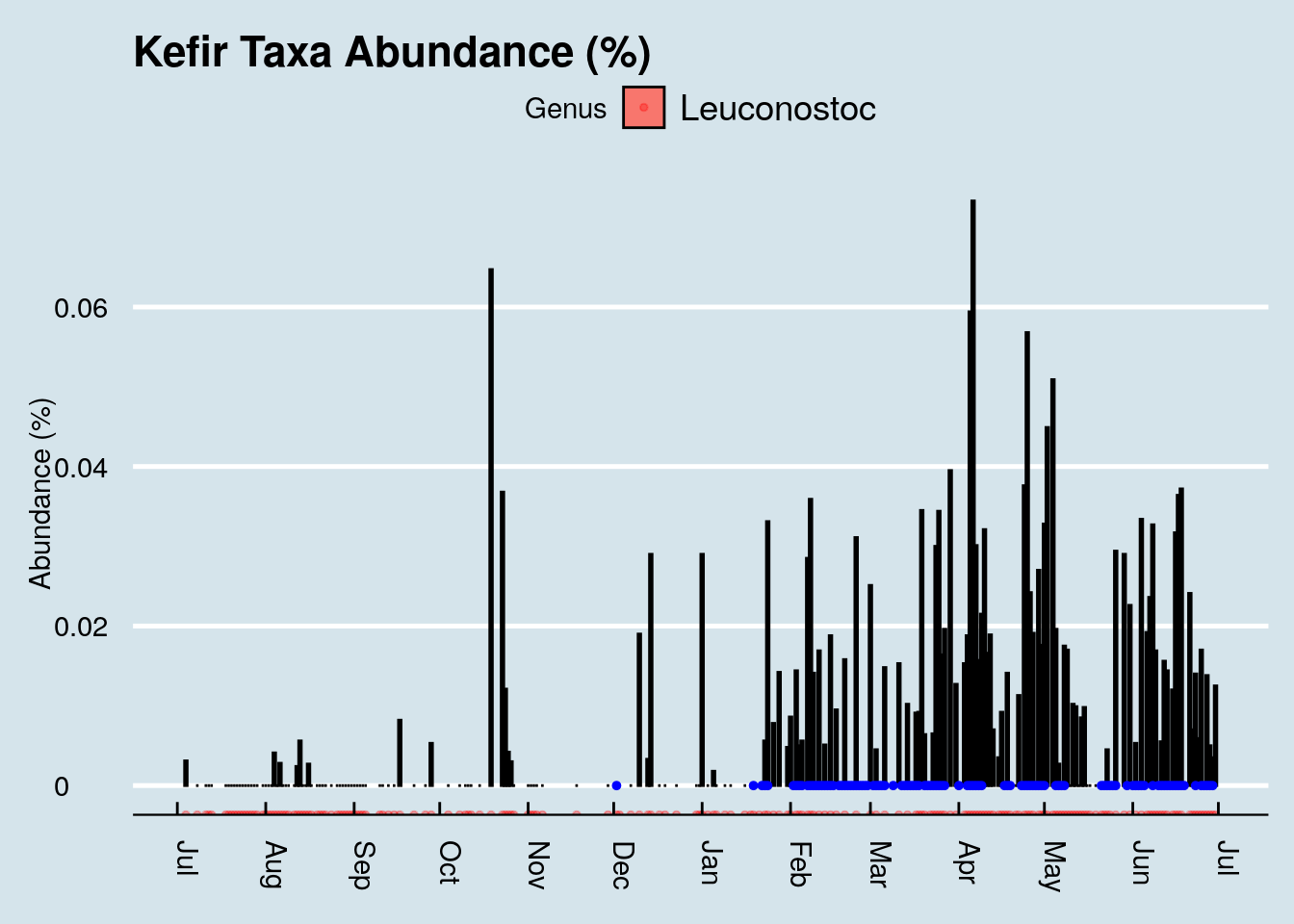

I’ve made milk kefir regularly by dropping kefir grains into milk and leaving it at room temperature for 24 hours. The grains multiply, requiring regular disposal of excess—a nice problem to have.

From my microbiome testing: when I drink kefir regularly, Leuconostoc jumps from near-zero to significant levels. Fusicatenibacter appeared only during kefir consumption periods—it wasn’t detectable otherwise.

Kombucha on the other hand, made no dent in my microbiome. I ran a week-long experiment drinking 48oz/day of GT’s Gingerade. Result? Bacillus coagulans (from the added probiotic) showed up transiently in my gut tests, but quickly disappeared.

The lesson: just because microbes from a fermented food show up in your gut doesn’t mean they’re doing anything obvious. The microbiome effects are detectable but their significance remains unclear—at least for a healthy person like me. My friend with chronic gut issues had a different experience, which suggests that individual variation matters enormously.

More About Fermentation

The 2021 eLife sourdough study that analyzed 500 starters from four continents—fascinating methodology and freely available data

The Sourdough Framework on GitHub: reproducible protocols for bread-making, written by a programmer for programmers

A Global Review of Geographical Diversity of Kefir Microbiome (2025): Comprehensive review of how kefir varies (and doesn’t vary) worldwide

My Personal Science Guide to the Microbiome, including detailed kefir and kombucha experiment protocols and results

Previous PSWeek posts: Bread/Sourdough, Coffee Metabolism, Apple Cider Vinegar

Personal Science Weekly Readings

We’ve been preaching for a long time that someday a personal scientist will win a nobel prize, but now thanks to LLMs it’s looking especially likely. AI Street summarized the state of AI discovering new science and says it’s looking pretty good.

At the national level, the United States has just launched the Genesis Mission, an attempt to build a scientific infrastructure in which AI helps drive simulation, data analysis, and experimental workflows. At the system level, platforms such as FutureHouse Kosmos and AI Scientist-v2 automate increasingly more of the research workflow. And at the level of active scientific projects, frontier models such as GPT-5 are already contributing concrete, verifiable steps across mathematics, physics, astronomy, biology, and materials science, as documented in OpenAI’s Early Science Acceleration Experiments.

About Personal Science

My friend's dramatic improvement from homemade kefir and my own measurable-but-imperceptible microbiome changes aren't contradictory—they're exactly what personal science predicts. Don’t rely on population-level studies that claim some affect; do your own experiment to see how it affects you.

Fermentation is an ideal way to start because the feedback is fast, the stakes are low, and the techniques are Lindy-tested. If something has kept humans alive for thousands of years, be skeptical of anyone telling you it's dangerous—but also be skeptical of anyone promising miracles. The only way to know what works for you is to try it.

Have you experimented with fermented foods? Questions or suggestions? Let us know.