Personal Science Week - 251127 Super Size Me

Radical food experiments

It’s one of the best-known personal science experiments of all time: Morgan Spurlock ate nothing but McDonalds for 30 days. The documentary he made, Super Size Me (2004), grossed $22 million on a $65,000 budget, earned an Oscar nomination, and was shown to schoolchildren across America as a cautionary tale.

This week we’ll review the film and its aftermath and discuss some more thoughts on food tracking.

The premise was simple: eat nothing but McDonald’s for 30 days and document what happens. By the end, Spurlock had gained 25 pounds, his cholesterol had spiked, his liver showed damage that his doctor compared to “an alcoholic’s after a binge,” and he claimed to be suffering mood swings and worse. McDonald’s discontinued the Super Size option six weeks after the film’s premiere.

The Replication Problem

Interestingly, multiple people have tried to replicate Spurlock’s results. Nobody has succeeded.

In 2006, Professor Fredrik Nyström at Sweden’s Linköping University ran the experiment with healthy medical students in their 20s. They ate nothing but fast food for 30 days. The results? Weight gain and decreased energy, yes—but none of the dramatic liver dysfunction or severe depression that Spurlock reported. The Swedish researchers concluded there must have been another cause for Spurlock’s extreme reaction.

Soso Whaley tried it in 2004 and lost 10 pounds while lowering her cholesterol from 237 to 197. Her secret? She exercised regularly and kept her caloric intake around 2,000 per day—rather than Spurlock’s claimed 5,000.

High school science teacher John Cisna lost 60 pounds eating exclusively at McDonald’s for 180 days. Again: portion control and exercise.

Twin Studies and microbiome scientist Tim Spector worked with his college-age son Tom to do a ten-day version of the Supersize Me diet: nothing but McDonalds (plus beer and chips). They measured his gut microbiome before, during, and after, finding a significant drop in gut diversity (who’d a thought eating a non-diverse diet could do that, duh?)

And then there’s the most remarkable case of all.

The Man Who Ate 35,000 Big Macs

Don Gorske, of my birth state of Wisconsin, had his first Big Mac on May 17, 1972. He ate nine that day. As of March 2025, he’s consumed over 35,000 of them—averaging about two per day for over 53 years.

He’s 71 years old. He weighs 185 pounds. His cholesterol is around 165 mg/dL (well below the 199 upper limit). His blood sugar is normal. His wife Mary, a registered nurse, reports that doctors consistently find him in excellent health.

Gorske appeared briefly in Super Size Me itself, though the documentary seemed to treat him as a curiosity rather than a counterexample. He skips the fries, walks six miles a day, and readily acknowledges he’s probably “blessed with a high metabolism.”

Is Gorske a genetic freak? Probably. But his existence is more proof that the relationship between fast food and health outcomes isn’t as simple as the documentary suggested.

Fathead: The Counter-Documentary

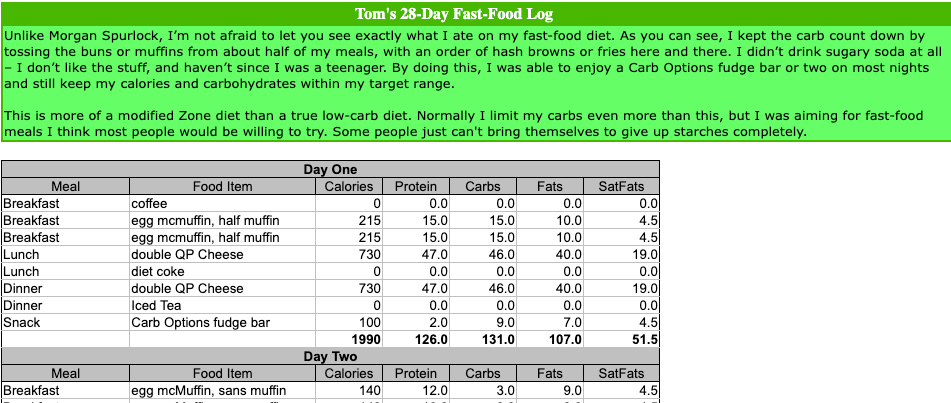

In 2009, comedian and former health writer Tom Naughton released Fat Head, a direct response to Super Size Me. His approach was different: he ate only fast food for 28 days, but limited himself to about 2,000 calories and 100 grams of carbohydrates daily. No calorie bombs, no mandatory Super Sizing.

The results? Naughton lost 12 pounds. His total cholesterol dropped without lowering his HDL (the “good” cholesterol). His triglycerides improved.

And, Naughton did something Spurlock refused to do: he published his complete food log online. You can verify every meal.

The film’s broader argument—that the problem isn’t fast food per se but rather the combination of excessive calories, processed carbohydrates, and sedentary behavior—has aged better than Super Size Me.

The Confession That Ruined It All

But the biggest problem with Super Size Me wasn’t discovered until years later.

In December 2017, amid the #MeToo movement, Spurlock released a statement titled “I Am Part of the Problem.” Among the revelations: he admitted he had been “consistently drinking since the age of 13” and “hadn’t been sober for more than a week in 30 years.”

Remember his doctor’s comment about his liver looking like “an alcoholic’s after a binge”? The doctor was right—just not for the reasons the documentary implied. Spurlock had told his physicians during the film that he didn’t drink. He also never released a food log documenting exactly what he ate during the experiment, despite multiple requests from critics.

Spurlock died in May 2024 at age 53 from cancer complications. The obituaries were mixed, acknowledging both the cultural impact of his work and the questions that now surround its scientific validity.

Personal Science and Eating

As always, the conclusion is that everyone is different and you should be skeptical about any diet advice that claims to apply to everyone. That’s why food and diet tracking are of long-running interest for all personal scientists. Here are a few Personal Science posts you may want to (re)read:

Spurlock clearly embellished his story to make for a viral documentary, but don’t pretend that professional scientists have a clean record either. See PSWeek250130 for our review of Big Science and its atrociously poor replication record. Our conclusion: any personal scientist who goes beyond popular headlines about food and health knows that virtually all of these studies are a waste of time.

See PSWeek241212 for our look into why nutrition labels are less accurate than you think—the FDA allows labels to be off by 20%, and Casey Neistat’s lab testing found actual calories exceeded labels by 500+ per day.

We looked at food sensitivity tests in PSWeek240411 and concluded that, like DNA-based diet recommendations, the current science is hardly better than trial-and-error.

Finally, see PSWeek250508 for some tips on why food-tracking is easier than you think. I regularly just speak an outline of my meals into an AI chatbot and get a summary at the end of the day.

Personal Science Weekly Readings

Speaking of radical diets, watch this short YouTube of what happened when Nick Norwitz ate 1000 sardines in a month. It raised his omega 3 levels to an unheard of healthy 12% but he started to smell like fish. He concludes that everyone should try “situational” fasting: test out a new diet when you’re in special circumstances, like a business trip.

You can watch Supersize Me and lots of other award-winning movies and documentaries for free on Kanopy. Use your public library card or university ID.

Fat Head documentary — Unfortunately not available on Kanopy or other free platforms but you can rent it for $4 on Apple and Amazon.

Finally, read this long Aeon Essay ‘I awoke at ½ past 7’, on how Victorians documented their lives, goes through old diaries to show an emerging awareness in the 19th century of writing daily notes on basics like sleep time, daily activities, and more. Many of us remember being intrigued by the Quantified Self movement with the realization that there are many of us who do these sorts of written and quantitative self-reflection. Apparently that’s been true for hundreds of years.

About Personal Science

Everyone is different, and you have to use the tools of science to figure out what works for you. That’s the core insight of personal science, and it applies whether you’re eating McDonald’s, sardines, or Thanksgiving turkey.

We publish each Thursday. If you have other topics you’d like to discuss, please let us know.

Thanks for clueing me in on the more likely real cause of Spurlock's fatty liver. I had always assumed it was the sugar in all that supersized soda.

When you consume sugar (sucrose), the sucrase enzyme splits it in two during the digestive process into fructose and glucose, both of which are readily absorbed. The glucose is indistinguishable from any other glucose molecule in your bloodstream and can be used as is by any cell in the body. However, the fructose has to be metabolized first in the liver before it can be used for energy by your body at large.

This does unfortunately wind up constituting a load on the liver, and alcohol is the only other common foodstuff that is handled similarly. Either can contribute to fatty liver - my perception is that alcohol is vastly more powerful, but because sugar is so much more widely overconsumed than alcohol (only 54% of Americans currently drink alcohol according to a recent WSJ article), I think sugar is most likely the root cause of the majority of the 90 million or so cases of fatty liver in the US.

Two books that discuss the negative aspects of fructose and/or sugar:

Fructose Exposed, M. Frank Lyons II, M.D., 2010. This author's thesis is that the human liver can only handle about 15g fructose per day (equivalent to 30g sugar), and fructose in foodstuffs besides sugar have the same problem. As an example, he lists 8 oz of unsweetened orange juice as containing 11.1 grams total fructose. I found the most useful aspect of the book to be these lists of the fructose content in a wide variety of foods.

Pure, White, and Deadly, John Yudkin, 1986. The author and his team at Queen Elizabeth College in London conducted countless experiments on lab animals and human volunteers during the mid-20th century comparing the effects upon health of sugar and starch. In most of the cases he reports, sugar was more harmful.

"decreased energy" This is a clear indicator of poor health and thus is really important.