Personal Science Week - 251009 Indirect Questioning

Get better answers from people who don't want you to know

When you want to know what people really think about sensitive topics—religion, race, drug use, tax evasion—asking directly will rarely give you their true answer.

This week we discuss ways to get more honest answers from people who won’t necessarily tell you directly.

Questioning the “Clock Boy”

In September 2015, 14-year-old Ahmed Mohamed brought a homemade digital clock to his Texas high school. His English teacher thought it looked like a bomb. Police handcuffed him, took him to juvenile detention, and fingerprinted him.

The incident exploded on Twitter as Americans quickly divided into those who thought the kid was being unfairly profiled, and those who thought the school was taking reasonable precautions to address a potential threat.

President Obama intervened with a tweet: “Cool clock, Ahmed. Want to bring it to the White House? We should inspire more kids like you to like science. It’s what makes America great.” Soon Mark Zuckerberg invited him to Facebook headquarters. Google invited him to their science fair. Twitter offered him an internship. An MIT professor suggested he was a shoo-in.

Personally I thought the whole thing was a big publicity stunt. I wanted the kid to be the real thing, a budding personal scientist persecuted for his experiments, but too much about the incident felt off: The “clock” was just commercial alarm clock guts stuffed into a pencil case. His father was a Sudanese political activist. The family was too quick to lawyer up and sue for $15 million.

I knew what my close friends thought, but how could I get an honest answer out of other people? Nobody wants to sound like a racist, an “Islamophobe”, or worse.

Here’s the measurement problem: You can’t expect normal people to give their honest opinion about a topic tinged with sensitive overtones. “Do you think Clock Boy is an aspiring engineer being treated unfairly?” People will give you the socially acceptable answer. You certainly can’t ask “What do you really think about Muslims” and expect honesty.

But what if you asked: “Among parents you know, what percentage would think the school was justified for handling the situation this way?”

Suddenly you’re not asking people to admit bias. You’re asking them to report what they observe in others. And here’s where it gets interesting: people tend to think others share their views more than they actually do—a bias psychologists call the false consensus effect. Heavy drinkers think everyone drinks heavily. Non-smokers think few people smoke. Their answer about “other parents” might reveal their own discomfort.

This is the core insight behind indirect questioning: when topics are sensitive, don’t ask directly.

The power of indirect questioning

I’ve done this for years. Instead of “Do you smoke marijuana?” I ask “What percentage of people your age smoke marijuana?” People who smoke think it’s common; people who don’t think it’s rare. In psychological terms, they “project”: they assume others are like them, and thus indirectly reveal their own hidden truths.

Or so I thought. Recently I’ve been digging into the research of when and how to use indirect questioning.

When you ask somebody “what percentage of your peers smoke marijuana,” their answer reflects two things you can’t separate:

Actual observation (genuine knowledge about peer behavior)

Projection (false consensus effect)

The problem: false consensus effect strength varies enormously by individual and context. A meta-analysis found effect sizes ranging from negligible to very strong: You can’t reliably invert the projection to extract true behavior.

One study comparing third-person phrasing (“how many of your friends...”) to direct questions found no significant difference for moderately sensitive topics like alcohol use. The false consensus backdoor only works when:

Behavior is highly stigmatized (creating large direct-vs-indirect gaps)

Respondents have limited actual knowledge about peer behavior (forcing projection)

You’re not trying to estimate individual behavior, just population trends

My casual “ask about others” approach works as a rough heuristic, not a measurement tool.

What works better than indirect questioning

It’s a little trickier to set up, but if you can do it, the “Randomized Response Technique” (RRT) is a better way to get truthful answers: each respondent privately performs a randomization. Based on the result, they either answer truthfully OR give a predetermined answer. The researcher never knows which path any individual took, but with enough responses, the population estimate is mathematically recoverable.

Example: say you’re distributing a survey, or maybe you’re speaking in front of a group.

Ask each person to flip a coin (or some other randomization with known probability).

Ask: “If heads, raise your hand. If tails and you [did the behavior], raise your hand.”

The math: if 240 out of 400 people raise hands, roughly 200 flipped heads (so raised hands regardless), meaning only 40 of the ~200 who flipped tails raised their hands—yielding 40/200 = 20% true rate.”

One good example of how this works is a 2014 Dutch study on cannabis use: researchers using RRT found that cannabis users reported an average of 17 marijuana cigarettes per year, as opposed to only 3 per year when asked directly—a nearly 6x higher admission rate.

There’s no perfect way to get inside somebody’s true thoughts. Even RRT has the problem that it’s difficult to explain, and you’ll need lots of responses to get a good picture.

But we’re personal scientists, not trying to get a big grant or fancy publication. Often these imperfect methods are just fine.

Personal Science Weekly Readings

A few items that show personal science in action:

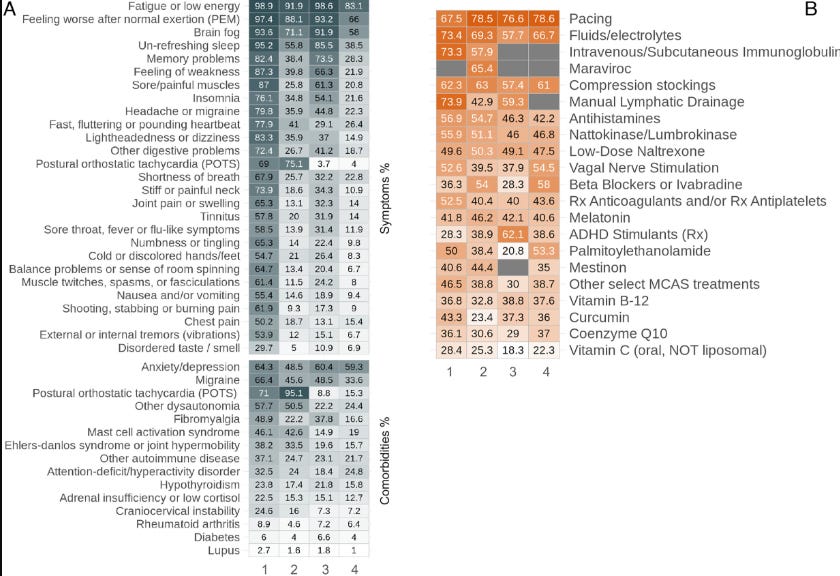

Patient-reported treatment outcomes in ME/CFS and long COVID An online study of 4000 ME/CFS and long COVID patients 150+ treatments concludes there’s a significant overlap in symptoms and treatment responses between conditions. Especially cool is the chart showing patient subgroups (like those with POTS co-morbidity) and treatments that seem to work for them (e.g. compression socks)

Speaking of studies, check People Science for some of the interesting trials that you can join.

A lengthy Aeon Essay Record Everything argues reasons to extensively record your life to enhance memory and personal identity.

Speaking of racism, how come people spend so much time protesting books in the school library, but nobody complains that standard textbooks in the sciences (even digital ones) are often 20 years out of date? See Hollis Robbins for details.

Epilogue: What Happened to Clock Boy

Many techies and scientists reached out to Ahmed with offers to collaborate on projects, but were disappointed. Tech entrepreneur Mark Cuban talked to him directly but came away unimpressed. The Mohamed family moved to Qatar shortly after the incident. They filed multiple lawsuits—against the school, the city, media personalities. By March 2018, all lawsuits were dismissed “with prejudice”, implying they were entirely without merit. The family was ordered to pay court costs. They remain in Qatar, where he is now in his late 20s, and he occasionally posts to Instagram , but nothing science- or technology-related.

About Personal Science

The Clock Boy incident showed how quickly people divide into camps—each side certain they see the truth clearly. But what if the better question isn’t “which side is right?” but “what methods might reveal what’s actually happening underneath the moral posturing?”

Many people associate scientific credentials—a degree, a titled position, peer review—with trustworthiness and truth. Others reject expertise entirely, trusting only their intuition. But personal scientists think truth-seeking is up to each of us, and that with the right attitude of open-minded skepticism, anyone can harness rigorous methods to solve everyday problems.

Sometimes that means acknowledging your direct question won’t work and getting creative with measurement. Sometimes it means recognizing that even clever indirect methods have limits. And sometimes it means accepting that behavioral observation reveals different truths than self-report—and neither is the whole story.

This weekly summary covers topics we think will interest anyone who uses science for personal rather than professional reasons.

What do you think other people think about Personal Science Week? Let us know.