Personal Science Week - 251002 Accidents

Great discoveries often come from people willing to make mistakes

Great scientific breakthroughs feel inevitable in hindsight. But the real history is messier and more encouraging: many of the most important discoveries happened by accident, noticed by people who were paying attention to the wrong results.

This week we look at the role of serendipity in science, and why personal scientists—unburdened by institutional constraints and publication pressure—are uniquely positioned to stumble upon their own “that’s funny...” moments.

The Luck of the Prepared Amateur

Ronald Ross wasn’t an entomologist—the only entomology book he owned was for anglers. For two years he dissected the wrong mosquito species, finding nothing. In August 1897, he tried a “dappled-winged” mosquito he’d noticed on a wall. That’s funny... these ones have pigmented cells in their stomachs. That observation, made on August 20, 1897, proved mosquitoes transmitted malaria. Nobel Prize 1902.

Dana Lewis couldn’t hear her continuous glucose monitor alarm while sleeping. That’s funny... why can’t I just make it louder? She built a custom alarm system that evolved into OpenAPS—the first DIY artificial pancreas. The FDA approved similar devices years later.

Brandy Deason wondered if her city really recycled plastic. That’s funny... let me put an AirTag in my recycling bin. It went straight to a storage facility. She exposed Houston’s greenwashing with $29 worth of Apple hardware. (See PSWeek241114)

These weren’t pure luck. As Isaac Asimov liked to say: “The most exciting phrase to hear in science, the one that heralds new discoveries, is not ‘Eureka!’ but ‘That’s funny...’”

Each required someone who was:

Actively doing something (not just theorizing)

Paying attention to unexpected results

Free to investigate without institutional barriers

Sound familiar? That’s exactly the advantage personal scientists have.

When Accidents Lead to Breakthroughs

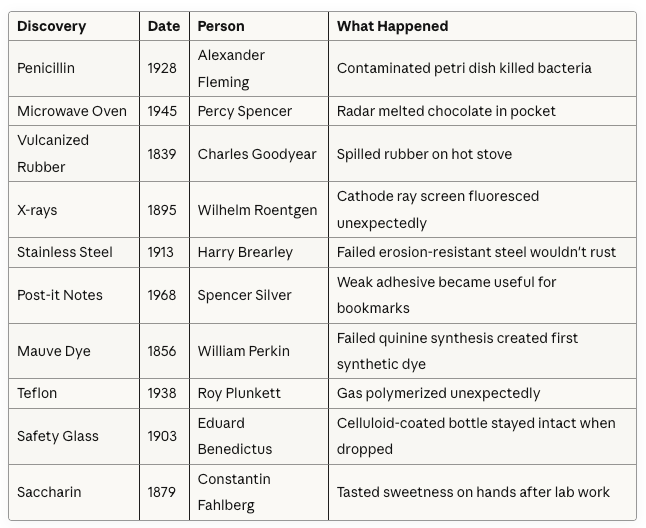

The excellent site Construction Physics recently published this list of accidental discoveries that changed the world:

Notice the pattern? These people were all actively experimenting. Zero experiments = zero chance of accidental discovery.

Professional Science Has Become Too Conservative

As we noted back in PSWeek240704, modern physics has a problem: researchers “mostly tap on their computers” rather than doing hands-on experiments. MIT’s Alexey Guzey concluded that “The current generation of theoretical physicists never made a real physical discovery and neither did their mentors.”

Even Noam Chomsky—arguably the greatest linguist ever—never did an actual experiment, according to MIT linguist Edward Gibson.

Professional science has become:

Slow (IRB approvals, peer review cycles)

Risk-averse (careers depend on “safe” publications)

Theory-heavy (computer models instead of tinkering)

Meanwhile, personal scientists can:

Run quick, cheap n=1 trials

Fail fast without career consequences

Notice “noise” that matters to you personally

The Advantage of Being an Outsider

William Perkin was 18 years old when he accidentally created the first synthetic dye. Professional chemists had already concluded it was impossible.

As we discussed in PSWeek240711, experts often dismiss amateurs using the Dunning-Kruger effect. But the research behind it is flawed—it’s mostly a statistical illusion. Sometimes not knowing what’s “supposed” to be impossible is exactly what lets you discover something new. Perkin didn’t know dye synthesis from coal tar was impossible. Ross didn’t know he needed to be an entomologist. Lewis didn’t know medical device hacking was “too hard.”

Even Experts Know Only a Tiny Part of Their Field

Philosopher of science Hasok Chang (PSWeek221013) observes how mainstream scientific ideas can be wrong, get suppressed, and remain underground for decades before being rediscovered.

My favorite example: phlogiston. Every chemistry student learns it was a mistaken theory triumphantly replaced by Lavoisier’s oxygen theory. Case closed, right?

Not quite. Chang discovered that long after its alleged demise, leading chemists continued to defend phlogiston—not as a theory of combustion, but as a coherent system for understanding chemical transformations.

The point isn’t that phlogiston was “right.” It’s that discarding it too hastily meant chemistry had to reinvent similar concepts later. Chang argues that abandoning phlogiston “deprived chemistry of important conceptual resources that had later to be developed anew through concepts such as electrons and chemical potential.”

By the late 18th century, some phlogistonists had identified phlogiston with hydrogen—they were actually onto something real about how substances transfer during reactions. If that line of thinking had continued, chemists might have discovered electrons decades earlier. Instead, the “wrong” theory got eliminated entirely, and science had to rediscover those insights from scratch.

Chang proposes “complementary science”—using historical investigation to recover lost knowledge that mainstream science abandoned too hastily. He literally recreated 18th-century experiments on boiling points that modern thermodynamics had supposedly rendered obsolete. Turns out the old observations were correct—and revealed phenomena that modern theory had oversimplified.

If even professional scientists working within established paradigms can miss important truths, imagine what personal scientists might discover by asking “stupid” questions that experts have learned not to ask.

Personal Scientists Can Do More Than They Think

We can call them “accidental discoveries” but maybe they’re not all that accidental.

1. Accidents favor the prepared and attentive

Fleming didn’t “get lucky” with penicillin. He was running experiments, noticed something unexpected, and investigated. Most people would have tossed the contaminated dish.

Personal scientists have this advantage: You’re not constrained by publication pressure or grant requirements. If you notice something weird, you can pivot immediately.

2. Small-scale experiments allow rapid iteration

Professional clinical trials take years and cost millions. Personal scientists can test, fail, and try again tomorrow. Goodyear tried thousands of rubber combinations before accidentally dropping one on a hot stove.

You create more opportunities for serendipity by doing more experiments.

3. You don’t need to cure cancer

The bar for personal science isn’t “publishable in Nature.” It’s “does this improve my life?”

As we emphasized in PSWeek240201, one negative study shouldn’t make you give up on a promising idea. If something seems promising, keep investigating.

4. Outliers are where the action is

Population studies tell you what works on average. But averages don’t matter if you’re the outlier. Remember that prebiotic study where individual responses varied wildly despite “statistically significant” averages? (PSWeek240201)

Your weird response might be the clue to something important.

5. “Wrong” ideas might not be wrong for you

Chang’s work reveals something crucial: what science declares “settled” often isn’t. Ideas get suppressed not because they’re false, but because they don’t fit the dominant paradigm.

Personal scientists don’t have to follow scientific consensus. If something works for you, it works—even if the mechanism isn’t understood or the idea is “discredited.”

The Next Great Discovery Might Be Yours

Nobody questions the usefulness of professional science. But it’s also become too slow, too conservative, too theory-driven. The spirit of tinkering—of noticing the unexpected and following curiosity—has largely moved to the amateurs.

You don’t need a PhD to run experiments. You don’t need IRB approval to test ideas on yourself. You don’t need a lab to track your sleep, measure your glucose, or optimize your productivity.

What you need is:

Willingness to try things (even if they might not work)

Attention to unexpected results (especially when they contradict expectations)

Freedom to follow hunches (without worrying about publication)

Patience to iterate (most “accidents” take years of experimentation)

Fleming didn’t plan to discover penicillin. Spencer didn’t set out to invent the microwave. Goodyear wasn’t trying to create vulcanized rubber that day. Ross dissected hundreds of mosquitoes before finding the right species.

They just kept experimenting until they noticed something interesting.

Remember Isaac Asimov’s words: “The most exciting phrase to hear in science, the one that heralds new discoveries, is not ‘Eureka!’ but ‘That’s funny...’”

Accidents don’t favor the passive. They favor the prepared amateur.

About Personal Science

Personal scientists approach health and wellness questions with systematic curiosity, focusing on problems that matter to us personally. Rather than wait for large-scale studies, we design our own experiments using careful observation and objective measurement.

Chang’s work reminds us that even well-established scientific knowledge can be incomplete or wrong. Ideas get suppressed, valuable knowledge gets lost, and what seems “settled” often isn’t. Personal science means being both open-minded and skeptical—willing to try “discredited” ideas while demanding evidence that they work for you.

We publish Personal Science every Thursday for anyone who believes the scientific method shouldn’t be limited to professionals. If you have other topics you’d like to discuss, let us know.

Well said Richard. Curiosity and Observation are the handmaids of discovery.