Personal Science Week - 250918 Pseudoscience

Personal science meets fake science, plus more links

Labeling somebody a pseudoscientist is an easy way to close off a discussion. After all, nobody would self-admit to being a pseudoscientist.

This week we’re thinking about the real meaning of pseudoscience and how personal scientists should react.

PSWeek has mentioned Trevor Klee and his Substack several times previously, notably for his attempts to create a product to get rid of forever chemicals. Like us, he takes science seriously and tries to practice the rationalist techniques of science in everyday life.

He recently wrote about The Dangers of Pseudoscience, in a thinly-veiled attack on U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F Kennedy Jr., who he accuses of using “ the verbiage and the reasoning style of a scientist (or at least scientist-adjacent person), but the goals of a lawyer.” Lawyers start with the conclusion (“He’s guilty!”) and work backwards, showing evidence that helps the case while downplaying or ignoring anything that doesn’t.

That’s not science.

Trevor’s piece is short, so he doesn’t give specific examples where RFKjr or MAHA are uniquely egregious. But I think the attacks are unfair; after all, RFKJr would never claim to be a scientist, pseudo or otherwise. In fact, he actually is a lawyer, where being a good public persuader is maybe the most important talent.

There’s more rigor in a Malcolm Gladwell’s Revisionist History podcast The RFKjr Problem (with transcript) that goes into exactly the level of detail I want to see in refuting some of RFKJr’s claims about vaccines. Specifically, they trace the source of his position that more children are harmed than helped by the infant rotavirus vaccine; the footnote intended to document it is incorrect, they say, and his case completely ignores a major study finding that the vaccine is safe.

Case closed, right? And at first the podcast convinced me that RFKjr is simply wrong. The most charitable defense you could give is that he screwed up on this one example and that we should not dismiss everything he says because of a mistake in a footnote. A less charitable explanation is that RFKjr is a dangerous charlatan who will cause untold suffering among the children whose parents are badly misinformed.

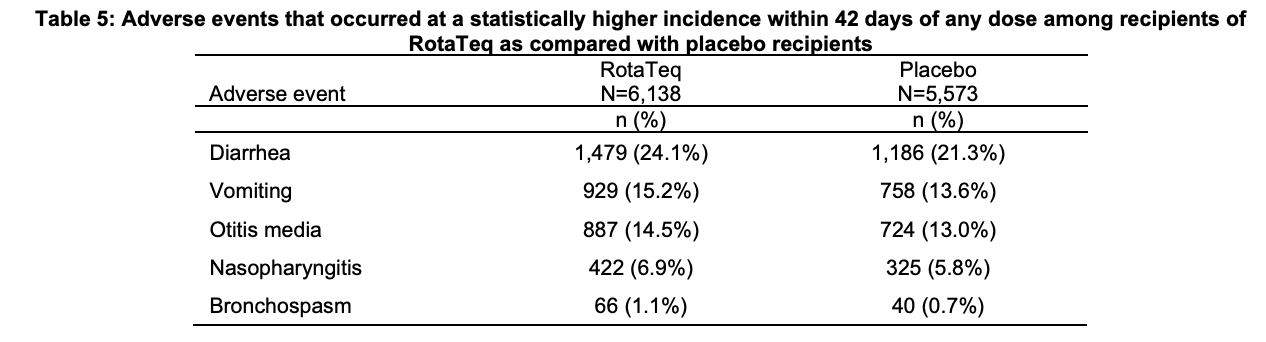

But here is the actual chart that RFKjr references in his claims about the rotavirus vaccine:

This chart is in the package insert for the vaccine, exactly where RFKjr said it would be. The Malcolm Gladwell podcast seems to ignore it, focusing instead on the number of deaths, which are roughly the same in both placebo (27) and vaccine (25) groups. In other words, there is no difference in deaths, despite a slightly higher rate of side effects in the vaccinated group. RFKjr is clearly wrong if he says that the vaccine is killing kids.

But wait! No difference in deaths? Then why take the vaccine? Especially since the FDA-mandated insert itself admits there is a statistically-significant risk of adverse effects.

So now what should I think? A source I trust — Malcolm Gladwell’s production team and interviews with numerous prominent virologists and epidemiologists —is clearly misinterpreting the words of somebody I’m told is a pseudoscientist I shouldn’t trust.

Pseudoscience vs Pseudo Engineering

Trevor concludes his thoughts on pseudoscience:

we are forced to rely on form over substance for almost everything we can’t check ourselves. Yes, engineering makes planes fly and careful science makes medicines work, but the average person isn’t going to go testing their planes or their medicines. They just make sure that the people flying the plane look like pilots, the people giving out the medicine look like pharmacists, and then trust that those people know what they’re doing.

But this is using the term “science” in multiple, inconsistent senses. True “science” (a search for truth) is different from “engineering” (practical solutions to problems).

RFKjr is not a scientist, pseudo- or otherwise. He’s certainly not an engineer whose credibility rests on whether some product actually works or not. When you conflate “science” with “engineering”, it’s easy to assume that the act of truth-seeking (science) is proven correct just because a separate activity (engineering) solves a problem.

A Personal Science Take on MAHA

I don’t know how RFKJr’s Make American Health Again (MAHA) initiatives will turn out. If overall health measures improve over the next several years, MAHA supporters will take credit for their policies; skeptics will counter that the improvements were due to something else. If health measures decline, the two sides will offer other explanations.

People decide who to believe before we decide what to believe. It’s ironic that the same sources who a few years ago warned against social media messages that contradicted the CDC may now do the exact opposite. If you can change your mind about the veracity of an information source, what was your basis for believing that source in the first place?

Ultimately we must trust people and information sources over which we have no direct control or interaction. I haven’t personally inspected the airplane I’m about to fly, but I’ve made enough similar flights safely that I just don’t think it’s worth the trouble to worry about this particular one.

Come to think of it, that’s a good example of the problem. No one can explain why planes stay in the air: Although the mathematical equations are well-understood, there is no good scientific explanation for why airplanes can fly. The standard theories taught in grad school – e.g. Bernoulli’s principle, Newton’s Laws – don’t account for some basic observations, like why a plane is able to fly upside down. Reminds us of Hasok Chang’s concept of “complementary science”: how science often abandons other plausible theories once a practical technology has been found. But those abandoned theories often contain insights that are still relevant. Even on matters we thought were long settled, it’s surprising how much remains to be explained.

Personal Science Weekly Readings

It’s easy to find mainstream sources that criticize RFKjr’s claims, particularly those about vaccines.

One summary I liked comes from Kevin C Klatt, a self-described Phd/RD and metabolism researcher whose July 2025 Substack post on 6 Months of MAHA gives a nice overview of the history of US public policy on nutrition, and a citation-heavy list of the stated hopes and problems of MAHA. The tldr is that he’s very critical, accusing MAHA leaders of wasting time on dubious (at best) and (likely) counterproductive proposals about vaccines, raw milk, and food dye while cutting budgets for child nutrition programs and worse.

The volume of anti-RFKjr sources makes it a little harder to find well-done sources that can defend the many controversial MAHA ideas out there, but there are two that I think are worth tracking. Trust the Evidence is written by two University of Oxford scientists; see their recent careful dissection of a BMJ editorial for a flavor of their approach. "Maryanne Damesi, reports" is a bit more provocative and should be read especially critically but if there’s somebody out there who can refute her careful research, I’d like to hear the counter-arguments.

Bluesky, the Twitter spinoff that briefly became popular among academic scientists who disagreed with Elon Musk’s political views, has stagnated. Nate Silver says it became a victim of what he calls “Blueskyism”: aggressive policing of dissent, a worship of credentialism, and an apocalyptic sense that the world is in an existential crisis.

X user Crémieux proposes the Law of Trends: “where there's a trend toward something rapidly increasing or decreasing, it's because we're recording things differently.” Our World in Data has examples about natural disasters, showing how standardized data collection didn’t start until the past fifty years or less, making it very difficult to compare with earlier aggregate statistics.

About Personal Science

Personal Scientists are skeptical about everything. It’s in our motto: Nullius in verba, the 1660 motto of the Royal Society: “take nobody’s word for it.”

Our newsletter is published each Thursday. If you have other topics that interest you, let us know.

"No difference in deaths? Then why take the vaccine?" To reduce the risk that you need to rush your infant to an emergency room with dehydration from severe diarrhea?