Personal Science Week - 250821 PFAS

Testing and filtering "forever chemicals"

You’ve probably heard of PFAS—the “forever chemicals” that persist in the environment and human body for years. But should you test for them? And if so, how?

This week I did a deep dive to see what I could learn from a personal science perspective.

The “Forever Chemicals” Problem

Regular readers will remember my previous exploration of water testing back in PSWeek250523, where I described my experience with basic home testing kits and the EWG Tap Water Database. Since then, the news has been full of discussions related to water issues, especially PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) and their possible association with health.

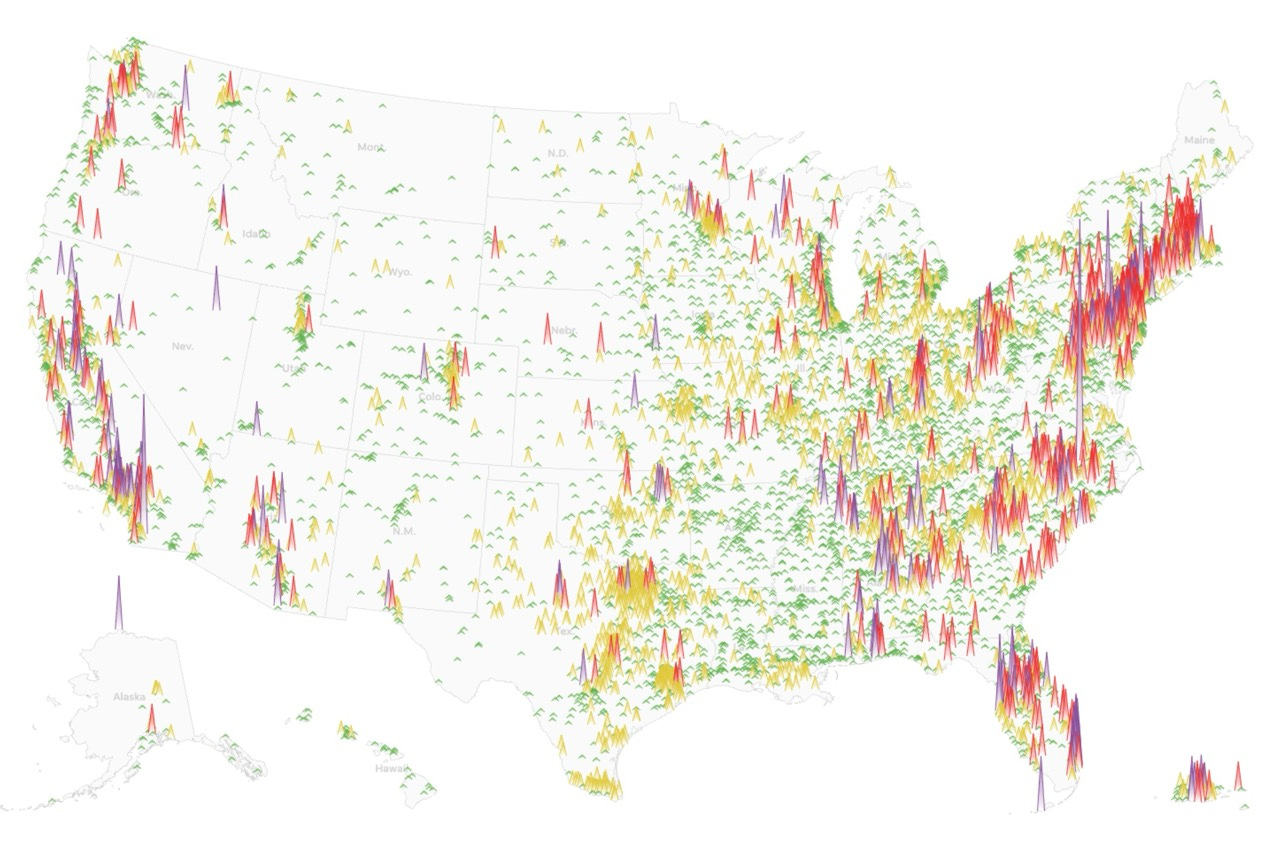

A new USA Today article about about PFAS includes a handy lookup tool that makes it easy to look up PFAS levels in local drinking water systems. You can see from the nationwide view that there’s quite a bit of variation in PFAS levels throughout the US (worst places are on the Eastern Seaboard).

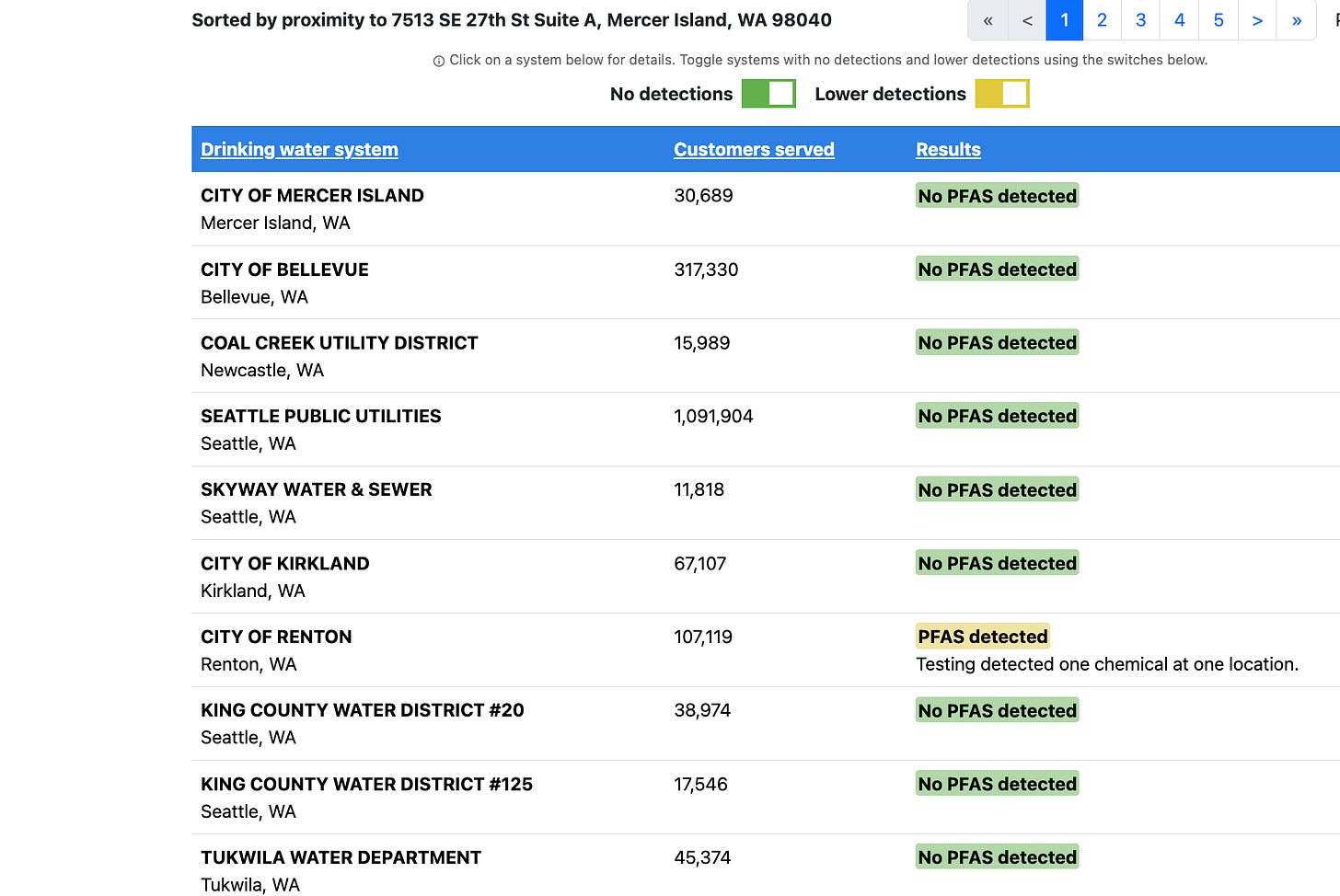

But as we personal scientists keep saying, national statistics are irrelevant to your own situation, so the first thing I did was ask it about PFAS levels in my own hometown:

Looks like I’m fine. But of course, who knows what happens between the time they tested and whatever shows up on the pipes into my house. To get a more accurate picture I’ll need to do some more precise testing.

What We Know (and Don’t Know) About PFAS Health Effects

But first, how dangerous are PFAS in the first place? As always, a skeptical review of professional publications shows contradictory and tentative results. When I did my first sanity check using an LLM, I found that knowledge about PFAS is evolving rapidly—and not always in the direction you might expect.

The Concerns: According to NHANES data, 96% of Americans have measurable PFAS in their blood. PFAS exposure has been linked to liver damage, immune system impacts, elevated cholesterol, kidney and testicular cancer (for PFOA specifically), and reproductive issues. Some scary research estimates that PFAS in drinking water contributes to 4,626-6,864 incident cancer cases per year in the US. But when I read such precise numbers, my skeptical alarm bells go off: I mean, how do they know it’s not 6,863? Is it possible that maaaybe the professionals who make those conclusions are just trying to sound more scientific when they don’t really know much?

The Plot Twist: Meanwhile, a 2025 review in Frontiers in Public Health challenges some of the earlier conclusions. The authors argue that recent epidemiological literature indicates “a lack of an association between PFOA exposure and risk of thyroid disease” and “no clear causal relationship” between PFOA and kidney cancer or thyroid disease. And that article didn’t even investigate the other claims from the initial scary studies, which may have claims that are just as dubious.

Meanwhile, the regulatory landscape remains in flux. In May 2025, EPA announced it would keep regulations for PFOA and PFOS but rescind regulations for four other PFAS compounds, extending compliance deadlines from 2029 to 2031. This suggests even regulators are struggling with the evolving science.

The Bottom Line: We have a rapidly evolving field where even basic cause-and-effect relationships remain contested. Worse, individual PFAS compounds may have very different effects, but most research lumps them together as a class.

Testing Options: Water vs. Blood

Regardless of whether or how bad these chemicals might be, can we at least get some clarity on the actual levels in our environment? Rather than rely on government testing, what can we learn for ourselves?

Water Testing

Building on my previous water testing experience, I’ve found several companies that offer comprehensive PFAS testing:

Cyclopure ($79): The most comprehensive option, testing 55 PFAS compounds including all 40 listed under EPA 1633, with detection limits as low as 1.0 ppt

TapScore/SimpleLab ($299): Tests 14 PFAS compounds using EPA 537.1 method, recommended by Consumer Reports and NY Times Wirecutter

TapScore GenX Test: ($600) Uses EPA 533 method for 25 compounds including newer PFAS like GenX.

Unlike the basic test strips I used in my previous checks, PFAS testing requires sophisticated chromatography and spectrometry equipment only available in professional labs—which of course costs more money. Since my local area seems well-tested already, I think I’ll spend my personal science budget elsewhere.

Blood Testing

How can we test for PFAS levels where it matters most — in your own body.

Last year I tried the $300 Function Health test (See PSWeek240912) but their standard test only looks at lead and mercury. PFAS is available as an add-on for an additional $300. I know biohackers who vouch for EmpowerDX ($300).

As with many diagnostics available to personal scientists, the lack of standards and regulatory enforcement means it’s hard to tell which blood tests are worth trying. Even if you trust the company or lab, their protocols are likely to be different from other labs, making direct comparisons difficult. Worse, if you’re relying on academic literature results to make judgements about risks, you’ll just confuse yourself if you don’t use the same lab and protocols written in whatever report you’re reading.

The CDC offers a Blood Level Estimation Tool that provides personalized estimates based on drinking water exposure data—useful without the cost and complexity of actual blood testing. Unfortunately the tool doesn’t work unless your zip code is one that the EPA has already checked.

If you’ve tried one of these tests let us know.

More PFAS-related Links

Plastic List Project Results: Nat Friedman’s crowdsourced testing found plastic chemicals in 86% of tested foods, with some truly awful outliers. (See more in PSWeek 250102)

Light Labs: DIY testing for PFAS and other contaminants in food ($100-200 for water testing)

Consumer Reports PFAS Filter Guide: Comprehensive testing of which water filters actually remove PFAS. Reasonable options include the brand ZeroWater, with pitchers that cost about $30.

Conclusion

PFAS testing represents a classic personal science dilemma: emerging science with conflicting evidence, testing methods with known limitations, and regulatory uncertainty. The personal science approach is to test water (your primary controllable exposure source) while maintaining healthy skepticism about definitive health claims.

Complete avoidance of PFAS isn’t possible—they’re too ubiquitous in the environment. But understanding your primary exposure sources gives you actionable data for reducing risk.

As always, be open-minded but skeptical. The PFAS story is still being written.

About Personal Science

Personal scientists prefer to figure things out for ourselves. We listen to experts not because they’re necessarily right, but because they’ve had more experience than the rest of us. Still, experts are often wrong and frequently disagree with one another, so whether you listen to experts or not, you’ll need to make up your own mind.

Natural philosophers were those, like Isaac Newton, who specifically applied themselves to understanding the physical world around us. Now that we have the word “scientist”, what do you call a philosophy that tries to apply rational thinking to every part of daily life? We call it Personal Science.

If you have other topics you’d like to discuss, please let us know.