Personal Science Week - 250731 Potpourri

Catching up on important personal science readings

We’ve been reading books, listening to podcasts, and noting other miscellaneous items of personal science interest.

This week is a dump of links and ideas we hope you’ll find interesting.

Podcasts and Books

The Infinite Loops podcast with Jim O’Shaughnessy is often a worthwhile listen, and naturally I perked up when they featured the author of a book titled Tiny Experiments. O’Shaughnessy, a former finance trader, admitted to his guest that “Even though I was a quant, I don’t believe in the Quantified Self”, and the interesting conversation that ensued made me think it would be a book about the pros and cons of personal science. The author, Anne-Laure Le Cunff, is a PhD neuroscientist who spent several years managing projects at Google until she started Ness Labs, to develop “simple tools to become the scientist of your own life.”

I ordered the book, but alas it turns out to be mostly a collection of self-help strategies: Focus on achievables, not goals (e.g. Instead of “I will lose 10 pounds”, say “I will walk 1000 more steps for 30 days”. ) Make procrastination your friend: ask the real reason you’re putting things off, and face it head on. (e.g. Why are you delaying that big presentation? Because you hate speaking in front of a group; so figure out how to make that easier).

Although the book wasn’t great personal science, I did like this great advice from O’Shaugnessy, quoting Ben Goodspeed: don’t confuse activity with effectiveness.

The bloodmarker company InsideTracker is popular among personal scientists for their comprehensive DTC tests, but they also run a regular podcast that’s worth adding to your feed. Longevity by Design does short 30-minute or so interviews with a range of people working on science related to longevity. This month I enjoyed a 1-hour discussion with investor Kurt Pfleger. He’s an early Google employee who has been funding longevity research for several years.

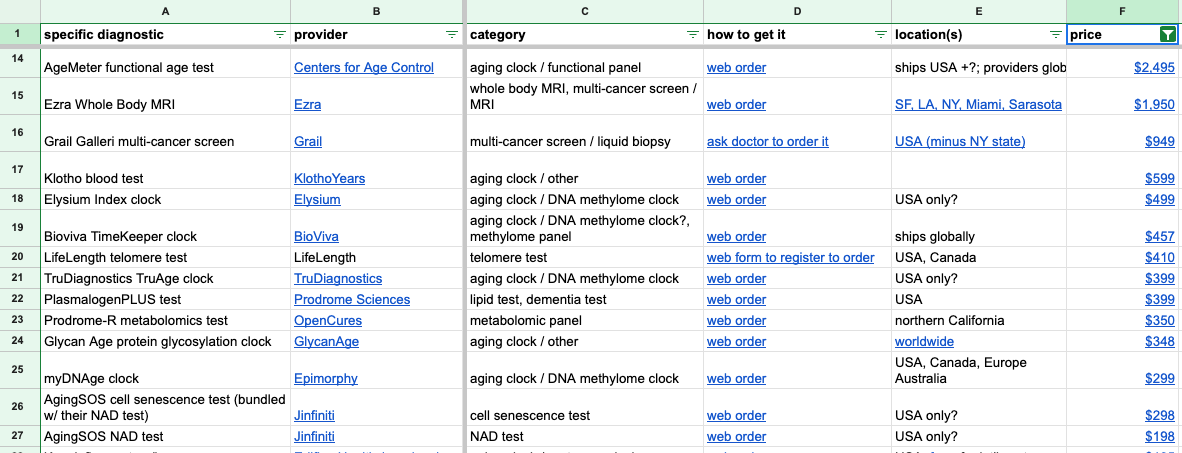

He now runs the website AgingBiotech.info, which he wants to be known as the single best resource for up-to-date information about longevity: books, podcasts, conferences, diagnostics …. they’re all carefully curated, mostly in Google Sheets lists.

Supplements

The best health-related podcast of all is Peter Attia’s, which comes with “ridiculously detailed” show notes if you pay the $20/month membership fee. But you’ll learn a ton just listening to the regular free podcasts. I especially liked a recent one on supplements, where he gave this framework for how to evaluate which to take:

The framework involves asking 6 key questions:

Are you taking this to correct a deficiency or achieve supraormal levels?

Are you taking this to improve lifespan or healthspan?

If for lifespan, is it targeting a specific disease? If for healthspan, which aspects are you hoping to improve?

Is there a biomarker you can track to determine the appropriate dose?

Do you understand the mechanism of action?

What is the balance of risk vs. reward, considering potential side effects, magnitude of effect, data quality, and supplement quality?

I’ll add that too many people take supplements because they read somewhere that such-and-such vitamin is important. That’s fine — it’s good to be curious and try new things — but how will you know whether the claim is true? A personal scientist looks at this as an opportunity to experiment.

Examine.com is an independent educational organization that claims to have the largest database of nutritional and supplement information on the internet. Elizabeth Van Nostrand studied their site and concluded that, while the summaries are well-done and extensive, they’re incomplete. “If a particular effect is important to you, you will still need to do your own research,” she concludes. (By the way, Elizabeth’s writing at Aceso Under Glass is a great resource for personal science in general, definitely worth following).

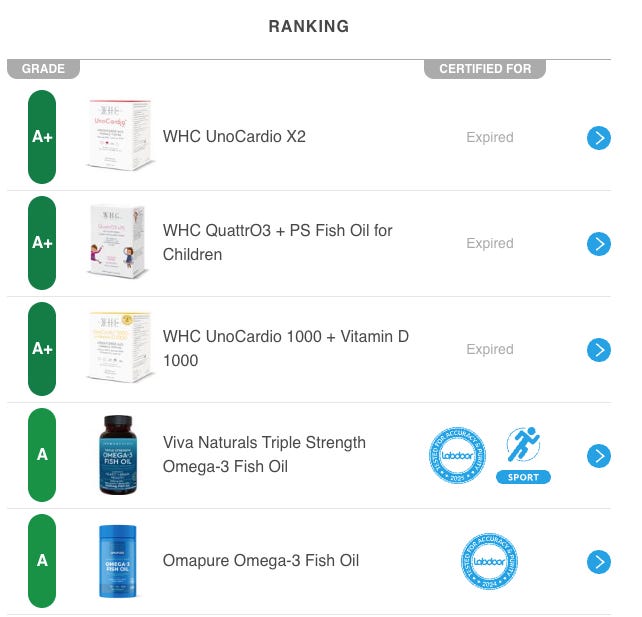

If you become interested in a particular supplement, please also check the reviews at Labdoor.com. Their independent technicians collect hundreds of off-the-shelf supplements and run them through laboratory-grade testing equipment to determine how closely the products meet the specs on the label. You can sort the results by quality as well as value.

For example, here’s how they rate various fish oils:

Interestingly, sometimes you can learn something about a supplement just by looking at the range in the rankings. For example, every one of the CoQ10 bottles tested came out as “A+” for having the amounts and purity claimed. I assume that’s because something about CoQ10 is pretty easy to manufacture and distribute with high quality?

About Personal Science

The supplement industry offers a perfect case study in why personal science matters. Even well-intentioned resources, like the books and podcasts mentioned here, can’t tell what will work for you—that requires your own systematic experimentation.

Personal scientists approach these decisions with the same methodical curiosity that drives professional research, but we focus on problems that matter to us individually. We design controlled experiments, track biomarkers when possible, and remain skeptical of both marketing claims and peer pressure from the biohacking community. Most importantly, we resist the temptation to generalize from our personal results to universal recommendations.

The real value isn't in finding the "optimal" supplement stack—it's in developing the analytical framework to evaluate claims systematically. Whether evaluating Peter Attia's six-question supplement framework or parsing conflicting research on sleep aids, the underlying skill is the same: maintaining open-minded skepticism while gathering data methodically.

Personal science acknowledges that professional research has serious limitations (replication crisis, publication bias, generalizability problems) without dismissing it entirely. Instead, we use published studies as hypotheses to test in our own carefully controlled n-of-1 experiments.

Nullius in verba—take no one's word for it, including ours. If you have other topics you’d like to discuss, please let us know.

I like the idea of looking at the Range of rankings - that is a helpful idea.

FWIW, one of my favorite supplement companies, Nootropics Depot, just had a public spat with Consumer Labs, another pay-to-rank supplement testing service. Apparently they disagreed over which analytical test was most appropriate. Apparently science is hard, and there is never just one "right answer"...